アメリカ

座標:

アメリカ合衆国 | |

|---|---|

国旗

紋章

| |

モットー: 「私たちは神を信じます」[1] | |

国歌: 「星条旗」 行進: 「星条旗は永遠に」[3] [4] | |

グレートシール:   | |

| |

米国とその領土 | |

| 資本 |

|

| 最大の都市 |

|

| 公用語 | 連邦レベルではなし[a] |

| 国語 | 英語 |

| 民族グループ (2018)[7] | レースで:

人種:

|

| Demonym(s) | アメリカ人[b] [8] |

| 政府 | 連邦 大統領 立憲共和国 |

• 大統領 | ドナルド・トランプ( R) |

• 副大統領[c] | マイク・ペンス( R) |

• ハウススピーカー | ナンシーペロシ( D) |

• 最高裁 | ジョン・ロバーツ |

| 立法府 | 会議 |

• 上院 | 上院 |

• 下院 | 衆議院 |

| 独立 イギリスから | |

• 宣言 | 1776年7月4日 |

• 連合の記事 | 1781年3月1日 |

• パリ条約 | 1783年9月3日 |

• 現在の憲法 | 1788年6月21日 |

• 権利章典 | 1789年9月25日 |

• 承認された最後の状態 | 1959年8月21日[d] |

• 最後の修正 | 1992年5月5日 |

| 範囲 | |

•総面積 | 3796742平方マイル(9833520キロ2)[E] [9] (3/4 ) |

• 水 (%) | 6.97 |

•総土地面積 | 3,531,905平方マイル(9,147,590 km 2) |

| 人口 | |

•2019年の見積もり | |

•2010年の国勢調査 | 308,745,538 [f] [10](3番目) |

•密度 | 87 /平方マイル(33.6 / km 2)(146番目) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2020年の見積もり |

•合計 | |

• 一人あたり | |

| GDP (名目) | 2020年の見積もり |

•合計 | |

• 一人あたり | |

| ジニ (2017) | ミディアム ・ 56番目 |

| HDI (2018) | 非常に高い ・ 15番目 |

| 通貨 | 米ドル($)(USD) |

| タイムゾーン | UTC −4から−12、+ 10、+ 11 |

•夏(夏時間) | UTC -4〜-10 [g] |

| 日付形式 |

|

| 主電源 | 120 V–60 Hz |

| 運転側 | 右[h] |

| 呼び出しコード | +1 |

| ISO 3166コード | 我ら |

| インターネットTLD |

|

アメリカ合衆国(USAとして一般的に知られている)、米国(米国または米国)やアメリカは、国で主に位置中心に北米間、カナダとメキシコ。それは50の州、連邦区、5つの主要な自治領、およびさまざまな所有物で構成されています。[i] 380万平方マイル(980万km 2)で、総面積で世界3番目または4番目に大きい国です。[e] 2019年の推定人口は3億2,800万人を超え、 [7]米国は世界で 3番目に人口の多い国です。アメリカ人は、何世紀にもわたる移民によって形成されてきた人種的、民族的に 多様な集団です。首都はワシントンDCであり、最も人口の多い都市はニューヨーク市です。

古インド 人は少なくとも12,000年前にシベリアから北米本土に移住し[19]、ヨーロッパの植民地化は16世紀に始まりました。アメリカ合衆国は東海岸沿いに設立された13のイギリス植民地から出現した。イギリスと植民地の間の多数の紛争は、1775年から1783年まで続くアメリカ独立戦争を引き起こし、独立をもたらしました。[20]は後半18世紀に始まり、米国が積極的に徐々に、北米全体に拡大し、新たな領土を獲得する、[21]アメリカ先住民を殺害し、変位 、そして新しい州を認める。 1848年までに、アメリカは大陸にまたがった。[21] 奴隷制は、 19世紀の後半まで、米国の多くでは合法だったアメリカ南北戦争がにつながったその廃止。[22] [23]

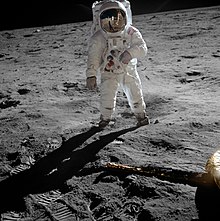

米西戦争と第一次世界大戦は、世界の大国として米国、の結果によって確認され、ステータス定着し、第二次世界大戦を。核兵器を開発した最初の国であり、核兵器を戦争で使用した唯一の国です。中は冷戦、米国とソ連はで競っ宇宙人種 1969で最高潮に達する、アポロ11号のミッション、最初に月面に人を上陸させた宇宙飛行。冷戦の終結と1991年のソビエト連邦の崩壊により、米国は世界の唯一の超大国となった。[24]

米国は連邦共和国であり、代表的な民主主義国家です。国連、世界銀行、国際通貨基金、アメリカ国家機構(OAS)、NATO、その他の国際機関の創設メンバーです。それは永久的なメンバーの国連安全保障理事会。

高度に開発された国である米国は世界最大の経済であり、世界の国内総生産(GDP)の約4分の1を占めています。[25]米国は世界で最大の輸入国と第二位の輸出国値による商品の、。[26] [27]その人口は世界全体のわずか4.3%ですが[28]世界の総資産の29.4%を保有しており、どの国でも最大のシェアを占めています。[29]所得と富の格差にもかかわらず、米国は引き続き非常に上位にランクされています平均賃金、中央値収入、中央値富、人間開発、一人当たりのGDP、労働者の生産性など、社会経済的パフォーマンスの測定値。[30] [31]それは何よりもある軍の3分の1以上作る、世界で電源グローバル軍事費、[32]と有力である政治的、文化的、そして科学的な国際力。[33]

語源

「アメリカ」という名前の最初の既知の使用法は、1507年に遡り、ドイツの地図製作者マーティンヴァルトゼーミュラーが作成した世界地図に登場しました。この地図では、イタリアの探検家アメリゴヴェスプッチに敬意を表して南アメリカに付けられた名前です。[34]彼の遠征から戻った後、ヴェスプッチは、最初と仮定西インド諸島は、当初で思ったように、アジアの東の限界を示すものではありませんでしたクリストファー・コロンブスが、代わりにヨーロッパへのこれまで未知の全く別の大陸の一部でした。[35] 1538年、フランドルの地図製作者ジェラルドゥスメルカトル彼自身の世界地図で「アメリカ」という名前を使い、それを西半球全体に適用しました。[36]

「アメリカ合衆国」というフレーズの最初の記録的な証拠は、スティーブンモイラン(Esq。)によって書かれたジョセフリード中佐、ジョージワシントンの補佐官でありマスター(マスター)マスターへの1776年1月2日の手紙に由来します。一般的な大陸軍。モイランは、革命的な戦争努力への援助を求めるために、「アメリカ合衆国からスペインへの全面的かつ十分な力をもって」行きたいという彼の望みを表明した。[37] [38] [39]「アメリカ合衆国」というフレーズの最初の既知の出版物は、1776年4月6日、バージニア州ウィリアムズバーグのバージニア・ガゼット新聞の匿名のエッセイにあった。[40]

第二草案連合規約によって調製ジョン・ディキンソンと遅くとも1776年6月17日より完成していないが、「この連盟の名前は『アメリカ合衆国ものでなければならないと宣言しました』」。[41]は後半に1777年に批准のための状態に送られた記事の最終版は、文「この連合の踏み段は、 『アメリカ合衆国ものでなければならないが含まれています』」。[42] 1776年6月、トーマスジェファーソンは独立宣言の「オリジナルのラフドラフト」の見出しに、すべて大文字で「UNITED STATES OF AMERICA」というフレーズを書いた。[41]この文書の草案は1776年6月21日まで浮上しませんでした。また、ディキンソンが6月17日の同盟草案でこの用語を使用する前と後のどちらで書かれたかは不明です。[41]

「米国」という短い形式も標準です。その他の一般的な形式は、「米国」、「米国」、および「アメリカ」です。口語名は「US of A」です。そして、国際的には「州」。 「コロンビア」は、18世紀後半の詩や歌で人気の名前であり、その起源はクリストファーコロンブスに由来します。 「コロンビア特別区」という名前で表示されます。コロンビアの国を含む、西半球の多くのランドマークや機関が彼の名前を冠しています。[43]

「合衆国」という語句はもともと複数形であり、独立国家の集まり、たとえば「合衆国はある」の説明であり、1865年に承認された米国憲法修正第13条に含まれています。[44]単数形-たとえば、「米国はある」—南北戦争の終結後、人気を博しました。単数形が標準になりました。複数形は、「これらの米国」というイディオムに保持されています。違いは使用法よりも重要です。状態のコレクションとユニットの違いです。[45]

米国の市民は「あるアメリカ。」「アメリカ」、「アメリカ」、「アメリカ」は形容詞的に国を指します(「アメリカの価値観」、「アメリカ軍」)。英語では、「アメリカ人」という言葉がアメリカと直接関係のないトピックや主題を指すことはほとんどありません。[46]

歴史

先住民族とコロンブス以前の歴史

北米の最初の住民がベーリングの陸橋を経由してシベリアから移住し、少なくとも12,000年前に到着したことは一般に認められています。しかし、証拠の増加はさらに早い到着を示唆しています。[19] [47] [48]陸橋を渡った後、古インド人は太平洋沿岸に沿って南下し[49]、氷のない内部の廊下を通った。[50]クローヴィス文化の周り11,000 BC登場、最初アメリカのヒト決済の最初の波を表すと考えられていました。[51] [52]約15,550年前にさかのぼるツールの最近の発見を含め、「pre-Clovis」文化についても証拠が増えています。これらは、北米への移住の3つの主要な波の最初のものを表している可能性があります。[53]

時が経つにつれ、北米の先住民の文化はますます複雑になり、南東部のコロンブス以前の ミシシッピ州の文化など、いくつかは高度な農業、壮大な建築、州レベルの社会を発展させました。[54]ミシシッピ州の文化は、南部で西暦800年から1600年まで栄え、メキシコとの国境からフロリダまで広がっていました。[55]その都市国家カホキアは、現代の米国で最大かつ最も複雑なコロンブス以前の遺跡です。[56]において、フォーコーナー領域、祖先プエブロの農業実験の世紀から開発培養。[57]

アメリカの3つのユネスコ世界遺産に登録されているのは、プエブロにあります。メサベルデ国立公園、チャコカルチャー国立歴史公園、タオスプエブロです。[58] [59]貧困点の文化のネイティブアメリカンが建設した土工工事も、ユネスコの世界遺産に指定されています。南部では五大湖地域、イロコイ連合は、第十二と15世紀の間にいくつかの時点で設立されました。[60]大西洋岸に沿って最も目立つのはアルゴンキンでした 狩猟と捕獲を練習した部族と、限られた耕作。

先住民への影響と相互作用

現代のアメリカ合衆国の領土におけるヨーロッパの植民地化の進展により、ネイティブアメリカンはしばしば征服され、追放されました。[61]ヨーロッパの到着後、アメリカの先住民はさまざまな理由で減少した[62] [63]主に天然痘およびはしかなどの疾患。[64] [65]

ヨーロッパとの接触時に北米の先住民を推定することは困難です。[66] [67] スミソニアン研究所のダグラスH.ウベラカーは、南大西洋州に人口92,916人、湾岸諸国に人口473,616人がいると推定している[68]が、ほとんどの学者はこの数値が低すぎると見なしている。[66]人類学者のヘンリーF.ドビンスは人口がはるかに多いと信じており、メキシコ湾の海岸沿いの1,100,000人、フロリダ州とマサチューセッツ州の間に住んでいる2,211,000人、ミシシッピ渓谷と支流に5,250,000人、そしてその中の697,000人を示唆しています。 フロリダ半島。[66] [67]

植民地化の初期の頃、多くのヨーロッパ人入植者は食糧不足、病気、そしてネイティブアメリカンからの攻撃を受けました。ネイティブアメリカンは、隣接する部族とも戦争を起こし、植民地戦争ではヨーロッパ人と同盟を結んでいた。しかし、多くの場合、原住民と入植者は互いに依存するようになりました。開拓者は食料と動物の毛皮と交換しました。銃、弾薬および他のヨーロッパの商品の原住民。[69]の原住民は、トウモロコシ、豆、スカッシュを育成するために、多くの入植者を教えてくれました。ヨーロッパの宣教師などは、インディアンを「文明化」することが重要であると感じ、ヨーロッパの農業技術とライフスタイルを採用するよう促しました。[70] [71]

ヨーロッパの入植地

北米でのヨーロッパの植民地化の進展により、ネイティブアメリカンは征服され、追放されることが多かった。[72]隣接する米国に到着した最初のヨーロッパ人は、1513年にフロリダを初めて訪れたファンポンセデレオンなどのスペインの征服者でした。それより以前に、クリストファーコロンブスは1493年の航海でプエルトリコに上陸しました。スペイン人は、セントオーガスティン[73]やサンタフェなどのフロリダとニューメキシコに最初の入植地を設立した。フランスも同様に独自のミシシッピ川。北米の東海岸で成功したイギリス人の入植地は、1607年のジェームズタウンのバージニア植民地と1620 年の巡礼者の プリマス植民地で始まりました。多くの開拓者が、宗教の自由を求めてやってきたキリスト教のグループに反対していました。大陸で最初に選出された立法議会であるバージニア州のバージェス邸は1619年に作成されました。下船する前に巡礼者によって署名されたメイフラワーコンパクトとコネチカット基本命令、アメリカの植民地全体に発展する代表的な自治と立憲主義のパターンの確立された先例。[74] [75]

他の産業が形成されたものの、すべてのコロニーのほとんどの入植者は小さな農家でした。換金作物には、タバコ、米、小麦が含まれていた。採掘産業は毛皮、漁業、製材業で育ちました。メーカーはラム酒と船を生産し、植民地時代後期までに、アメリカ人は世界の鉄供給の7分の1を生産していました。[76]結局、都市は沿岸に点在し、地方経済を支え、貿易ハブとして機能した。イギリス人入植者たちはスコッチアイリッシュの移民や他のグループの波によって補足された。沿岸の土地がより高くなるにつれて、解放された年季奉公人たちは、さらに西の土地を要求した。[77]

イギリスの民間人との大規模な奴隷貿易が始まった。[78]病気が減り、食事と治療が改善されたため、奴隷の平均余命は北米でははるか南よりはるかに高く、奴隷の数は急速に増加した。[79] [80]植民地社会は、奴隷制の宗教的および道徳的含意について大部分が分かれており、植民地は慣習に賛成または反対する行為を可決した。[81] [82]しかし、18世紀の初めまでに、アフリカの奴隷は、特に南部において、作物作物労働のために年季奉公人に取って代わっていた。[83]

1732年にジョージア州が樹立され、アメリカ合衆国になる13の植民地はイギリスによって海外依存として管理されました。[84]すべてはそれにもかかわらず、選挙と地方政府は、最も自由な男性に開いていました。[85]出生率が非常に高く、死亡率が低く、定住が安定しているため、植民地の人口は急速に増加した。比較的少数のネイティブアメリカンの人口が日食になりました。[86]大覚醒として知られる1730年代と1740年代のキリスト教復興運動は、宗教と宗教的自由の両方への関心を高めた。[87]

中に七年戦争(として米国で知られているフレンチ・インディアン戦争)、イギリス軍は、フランスからカナダを押収したが、フランス語圏の人口は、政治的に南部のコロニーから単離したまま。征服され強制退去させられたネイティブアメリカンを除くと、13のイギリスの植民地は1770年に210万人を超え、イギリスの約3分の1でした。新しい到着が続いているにもかかわらず、自然な増加率は1770年代までにごく少数のアメリカ人だけが海外で生まれたほどでした。[88]植民地とイギリスからの距離は自治の発展を可能にしたが、彼らの前例のない成功は君主を動機づけた王権を再主張することを定期的に求めること。[89]

1774年、フアンペレス配下のスペイン海軍の船サンティアゴが、現在のブリティッシュコロンビア州のバンクーバー島ヌートカ湾の入り江に進入し、停泊しました。スペインは着陸しなかったが、原住民は、貿易に船にパドル毛皮のためのアワビからシェルカリフォルニア。[90]当時、スペイン人はアジアと北アメリカの間の貿易を独占することができ、ポルトガル人に限られた許可を与えていました。ロシア人がアラスカで成長している毛皮取引システムを確立し始めたとき、スペイン人はロシア人に挑戦し始め、ペレスの航海は太平洋岸北西部への多くの最初のものでした。[91] [j]

彼の中に3番目と最後の航海、キャプテン・クックがハワイとの正式な接触を開始するために最初のヨーロッパ人となりました。[93]キャプテンクックの最後の航海を探し、北米とアラスカの海岸に沿って航行含ま北西航路約9カ月間を。[94]

独立と拡大(1776–1865)

アメリカ独立戦争は、欧州の消費電力に対する独立の最初の成功植民地戦争でした。アメリカ人は「共和主義」のイデオロギーを発展させ、政府は地元の議会で表明されているように人々の意志に頼っていたと主張した。彼らはイギリス人としての権利と「代理人なしの課税なし」を要求した。イギリスは議会を通じて帝国を管理することを主張し、紛争は戦争にエスカレートしました。[95]

第二次大陸会議は満場一致で独立宣言を採択し、イギリスはアメリカ人の不可侵の権利を保護していないと主張しました。7月4日は毎年独立記念日として祝われます。[96] 1777年、連合の記事は 1789年まで作動分散化政府確立し[96]

1781年にヨークタウンで決定的なフランス系アメリカ人が勝利した後[97]、イギリスは1783年の平和条約に署名し、アメリカの主権が国際的に認められ、ミシシッピ川の東側にすべての土地が与えられた。民族主義者が主導フィラデルフィアコンベンション書面で1787のを合衆国憲法、批准連邦政府は1789年に、有益なチェック・アンド・バランスを作成するための原則に、3つの分岐に再編された1788年に状態規則にジョージ・ワシントン率いていました、大陸軍が勝利し、初代大統領となった新憲法の下で選出された。権利章典は、連邦制限禁止、個人の自由をし、法的保護の範囲を保証し、1791年に採択された[98]

連邦政府は1808年に国際奴隷貿易を犯罪としましたが、1820年以降、高収益性の綿作物の栽培がディープサウスで爆発し、それに伴って奴隷人口も爆発しました。[99] [100] [101]第二大覚醒、特に1800–1840は、数百万人を福音主義的プロテスタンティズムに改宗させた。北部では、奴隷制度廃止運動を含む複数の社会改革運動を活性化させた。[102]南部では、メソジストとバプテストが奴隷集団の間で改宗した。[103]

アメリカ人の西への拡大への熱心さは、アメリカインディアン戦争の長いシリーズを引き起こしました。[104]ルイジアナ買収 1803年のフランス、主張領土のは、ほとんどの国の面積を倍増しました。[105] 1812年の戦争は、さまざまな不満をめぐってイギリスに対して宣言され、引き分けのために戦い、アメリカのナショナリズムを強化した。[106]フロリダ州への軍事侵略の一連の主導譲るためにスペインを 1819年にそれと他の湾岸地域を[107]拡大はによって助けられたスチームパワー、蒸気船アメリカの大規模な水系に沿って移動し始め、その多くはエリーやI&Mなどの新しい運河でつながっていました。その後、さらに速い鉄道が国土全体に広がり始めました。[108]

1820年から1850年にかけて、ジャクソンの民主主義は一連の改革を開始しました。それはの上昇につながった第二者システム 1828から1854年ザ・に支配的な政党として民主党とホイッグ党の涙の道 1830年代では、例示したインドの削除ポリシーを強制的に西にインド人を再定住することをインドの予約。米国は1845年に拡張主義のマニフェストの運命の期間中にテキサス共和国を併合しました。[109] 1846年のイギリスとのオレゴン条約は、現在のアメリカ北西部の米国による支配につながった。[110]メキシコとアメリカの戦争で勝利した結果、1848年のカリフォルニアのメキシコ分裂と現在のアメリカ南西部の大部分が生まれました。[111] 1848年から49年にかけて のカリフォルニアゴールドラッシュは太平洋沿岸への移住を促進し、それがカリフォルニア大虐殺[112] [113] [114] [115]と追加の西部州の創設につながりました。[116]南北戦争後、新しい大陸横断鉄道の入植者のために移転容易に作られたが、内部の貿易を拡大し、アメリカ先住民との競合を増加させました。[117] 1869年、新しい平和政策名目上、ネイティブアメリカンを虐待から保護し、さらなる戦争を避け、最終的な米国市民権を確保すると約束した。それにもかかわらず、大規模な紛争は1900年代まで西洋中ずっと続いた。

南北戦争と復興時代

相いれ断面紛争奴隷のアフリカ人とアフリカ系アメリカ人は、最終的に導いたアメリカ南北戦争。[118]当初、連合に加盟する州は上院で部分的な均衡を保ち、奴隷と自由州を交互にしたが、自由州は人口と下院で奴隷州を上回っていた。しかし、西部の領土が追加され、自由土壌国家が増えるにつれ、奴隷制を拡張するか制限するかと同様に、連邦制と領土の処分をめぐる議論で奴隷国家と自由国家の間の緊張が高まりました。[119]

1860年の共和党の アブラハムリンカーンの選挙により、13の奴隷国家の会議が最終的に離脱を宣言し、アメリカ連合国(「南」または「連邦」)を形成しましたが、連邦政府(「連合」)はその離脱を維持した違法。[119]は、この離脱をもたらすために、軍事行動はsecessionistsによって開始された、と連合は親切に答えました。その後の戦争はアメリカ史上最も致命的な軍事紛争となり、多くの民間人だけでなく約618,000人の兵士が死亡する結果となった。[120]連合は当初、単に国を統一し続けるために戦った。それでも、1863年以降に犠牲者が出てリンカーンが解放宣言を発表したため、北軍の視点から見た戦争の主な目的は奴隷制の廃止になった。実際、1865年4月に最終的に北軍が戦争に勝利したとき、敗北した南部の各州は奴隷制を禁止した修正第13号を批准する必要がありました。

政府が制定された3つの憲法改正前述の第十三など:戦後数年で修正第14条をほぼ4百万の市民権を提供するアフリカ系アメリカ人の奴隷、されていた[121]及び第十五改正は、アフリカ系アメリカ人が持っていたことを理論的に保証します選挙権。戦争とその解決により、新しく解放された奴隷の権利を保証しながら南部の再統合と再建を目指す連邦政府の力が大幅に増加しました[122]。

戦後、本格的な復興が始まりました。リンカーン大統領は北軍と元同盟の間の友情と許しを促進しようとしたが、1865年4月14日の彼の暗殺は、再び南北間のくさびを動かした。連邦政府の共和党は、南部の再建を監督し、アフリカ系アメリカ人の権利を確保することを目標にした。民主党が1876年の大統領選挙を認めるために、共和党が南部のアフリカ系アメリカ人の権利の保護をやめることに同意した1877年の妥協まで、彼らは続いた。

南部の白人民主党員は、自分たちを「救い主」と呼び、復興の終結後、南部を支配した。1890年から1910年にリディーマーは、いわゆる確立ジム・クロウ法を、disenfranchising地域全体で最も黒人といくつかの貧しい白人が。黒人は、特に南部で人種差別に直面しました。[123]彼らは時折リンチを含む自警団の暴力を経験した。[124]

さらなる移民、拡大、および工業化

北部では、都市化と南および東ヨーロッパからの前例のない移民の流入が国の工業化に余剰労働力を供給し、その文化を変革しました。[126]電信や大陸横断鉄道を含む国家のインフラストラクチャーは、アメリカの旧西部の経済成長とより大きな和解と発展に拍車をかけました。後の電灯と電話の発明は、通信と都市生活にも影響を及ぼします。[127]

米国が戦ったインディアン戦争 1810年から少なくとも1890年にミシシッピ川の西側を[128]これらの競合のほとんどをネイティブアメリカンの領土の割譲とへの閉じ込めで終わったインディアン居留。これにより、機械栽培の作付面積がさらに拡大し、国際市場の余剰が増加しました。[129]本土の拡大も含まアラスカの購入からロシア 1867年における[130] 1893年に、ハワイで親米の要素が倒した君主制をして形成されるハワイの共和国米国は、併合 1898年を。プエルトリコ、グアム、およびフィリピンは、スペインとアメリカの戦争に続いて、同じ年にスペインによって割譲されました。[131] アメリカ領サモアは、第二次サモア内戦の終結後の1900年に米国に買収されました。[132]米領バージン諸島は 1917年にデンマークから購入した[133]

19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけての急速な経済発展は、多くの著名な実業家の台頭を促しました。大物実業家のようなコーネリアスヴァンダービルト、ジョン・D・ロックフェラー、そしてアンドリュー・カーネギーは、中国の進歩主導鉄道、石油、および鉄鋼産業を。銀行業は経済の主要な部分となり、JPモーガンが注目に値する役割を果たしました。アメリカ経済は急成長し、世界最大の経済となり、アメリカは大きな権力の地位を獲得しました。[134]これらの劇的な変化は社会不安とポピュリストの台頭を伴っていた、社会主義、アナキズム運動。[135]この期間は、女性参政権、アルコール禁止、消費財の規制、競争を確実にするためのより大きな独占禁止法および労働者の状況への注意を含む重要な改革を見た進歩的な時代の到来で結局終わった。[136] [137] [138]

第一次世界大戦、大恐慌、第二次世界大戦

アメリカ合衆国は、1914年の第一次世界大戦の勃発から1917年まで中立のままで、正式な第一次世界大戦の同盟国とともに「関連勢力」として戦争に参加し、中央大国に対する流れを変えるのを助けました。 1919年、ウッドローウィルソン大統領はパリ平和会議で主導的な外交的役割を果たし、米国が国際連盟に参加することを強く主張しました。しかし、上院はこれを承認することを拒否し、国際連盟を設立したベルサイユ条約を批准しなかった。[139]

1920年、女性の権利運動は、女性の参政権を認める憲法改正案を可決した。[140] 1920年代と1930年代には、マスコミュニケーション用のラジオの台頭と初期のテレビの発明がありました。[141]活発な20代の繁栄は、1929年のウォールストリートクラッシュと大恐慌の始まりで終わりました。 1932年に大統領に選出された後、フランクリンD.ルーズベルトはニューディールで対応した。[142]ザ・グレート・マイグレーションアメリカ南部の何百万ものアフリカ系アメリカ人が第一次世界大戦前に始まり、1960年代まで拡大しました。[143]に対し、ダストボウル 1930年代半ばのは、多くの農村を疲弊と西部の移行の新しい波に拍車をかけました。[144]

第二次世界大戦中、最初は事実上中立でしたが、米国はレンドリースプログラムを通じて1941年3月に連合国に資材を供給し始めました。 1941年12月7日、日本帝国はパールハーバーに奇襲攻撃を仕掛け、米国は枢軸国勢力に対して連合国に加わるよう促しました。[145]日本は最初にアメリカを攻撃したが、それでもアメリカは「ヨーロッパ初」の防衛政策を追求した。[146]このようにして、アメリカは広大なアジアの植民地であるフィリピンを離れ、孤立し、敗戦と戦っていた。軍事資源がヨーロッパの劇場に捧げられたので、日本の侵略と占領。戦争中、アメリカはイギリス、ソビエト連邦、中国とともに戦後の世界を計画するために集まった同盟国勢力の「4人の警官」[147]の1人と呼ばれました。[148] [149]国民は約40万人の軍人を失ったが[150]戦争から比較的無傷で浮上し、経済的および軍事的影響力がさらに高まった。[151]

米国は、英国、ソビエト連邦、およびその他の同盟国とのブレトンウッズおよびヤルタ会議で主導的な役割を果たし、新しい国際金融機関とヨーロッパの戦後再編に関する協定に署名しました。連合軍の勝利は、ヨーロッパで優勝した 1945年の国際会議で開催されたサンフランシスコは、生産国連憲章戦争後にアクティブになりました、。[152]米国と日本は、その後の歴史の中で最大の海戦でお互いを戦ったレイテ沖海戦。[153] [154]米国は最終的に最初の核兵器であり、広島と長崎の都市で日本でそれらを使用した。日本人は第二次世界大戦を終わらせた9月2日に降伏した。[155] [156]

冷戦と公民権時代

第二次世界大戦後、米国とソビエト連邦は、冷戦と呼ばれるようになった時代に、資本主義と共産主義の間のイデオロギー的格差に牽引され、権力、影響力、名声をめぐって争いました。[157]彼らはヨーロッパの軍事問題を支配し、一方はアメリカとそのNATO同盟国であり、もう一方はソ連とそのワルシャワ条約機構同盟国であった。米国は共産主義の影響力拡大に向けた封じ込め政策を策定しました。米国とソビエト連邦が代理戦争を行っている間 強力な核兵器を開発し、両国は直接の軍事紛争を回避しました。

米国は、ソビエトが後援していると見なした第三世界運動にしばしば反対し、時折、左翼政府に対する政権交代のための直接行動を追求し、時には右翼権威主義政府をも支援した。[158] 1950-53年の朝鮮戦争でアメリカ軍は共産主義の中国軍と北朝鮮軍と戦った。[159]はのソ連の1957打ち上げ最初の人工衛星とのその1961年打ち上げ最初の有人宇宙飛行は、「開始宇宙競争、米国は最初の国になっている」マン・オン・ザ・ムーンを着陸を1969年に[159]東南アジアにおける代理戦争は結局として、フルアメリカン参加へと進化し、ベトナム戦争。

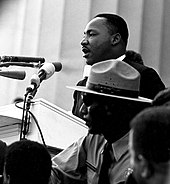

家庭では、米国は持続的な経済拡大と、その人口と中産階級の急速な成長を経験しました。州間高速道路システムの建設は、その後数十年にわたって国のインフラを変革しました。何百万人もが農場や都心から郊外の大規模住宅開発に移りました。[160] [161] 1959年にハワイは50番目になり、最後に米国の州が加わった。[162]成長している公民権運動は、非暴力を用いて、人種差別と差別に対抗し、マーティンルーサーキングジュニアと対決しました。著名なリーダーと名目になります。1968年の公民権法で最高潮に達した裁判所の決定と法律の組み合わせは、人種差別を終わらせることを目指しました。[163] [164] [165]一方で、ベトナム戦争、黒人ナショナリズム、および性革命への反対によって燃料を供給された反文化運動が成長した。

「貧困との戦い」の開始により、資格と福祉支出が拡大しました。これには、メディケアとメディケイドの作成、高齢者と貧困者にそれぞれ健康保険を提供する2つのプログラム、手段テスト済みの フードスタンププログラムと家族への援助が含まれます。扶養の子ども。[166]

1970年代から1980年代初頭にかけて、スタグフレーションが始まりました。 1980年の選挙後、ロナルドレーガン大統領は自由市場志向の改革で経済停滞に対応しました。デタントの崩壊後、彼は「封じ込め」を放棄し、ソ連へのより積極的な「ロールバック」戦略を開始しました。[167] [168] [169] [170] [171]過去10年間に女性の労働参加が急増した後、1985年までに16歳以上の女性の大半が雇用されました。[172]

1980年代後半はソ連との関係に「融け」をもたらし、1991年の崩壊はついに冷戦を終わらせた。[173] [174] [175] [176]これは単極化[177]をもたらし、米国は世界の主要な超大国としての挑戦を受けた。第二次世界大戦後の時代に登場したパックス・アメリカーナのコンセプトは、冷戦後の新世界秩序の用語として広く知られるようになりました。

現代史

冷戦後、1990年にサダムフセイン政権下のイラクが侵略し、米国の同盟国であるクウェートを併合しようとしたとき、中東での紛争が危機を引き起こしました。不安定さが他の地域にも広がるのではないかと恐れて、ジョージHWブッシュ大統領は湾岸戦争と題されたステージングでサウジアラビアに防衛部隊を編成する作戦砂漠シールドと作戦砂漠ストームを立ち上げた。クウェートからのイラク軍の追放と君主制の回復で終わるイラクに対する米国に率いられた34カ国からの連合軍によって賭けられた。[178]

米軍の防衛ネットワーク内で発生したインターネットは、1990年代に国際的な学術プラットフォームに広まり、世界の経済、社会、文化に大きな影響を与えました。[179]に起因して、ドットコムブーム、安定した金融政策、および減少社会福祉支出、1990年代には見最長の景気拡大現代の米国の歴史の中では。[180] 1994年以降、米国は北米自由貿易協定(NAFTA)を締結し、米国、カナダ、メキシコ間の貿易が急増しました。[181]

で2001年9月11日、アルカイダのテロリストが襲った世界貿易センターニューヨークやペンタゴンを約3,000人が死亡、ワシントンD.C.の近く。[182]これに応じて、米国は対テロ戦争を開始しました。これにはアフガニスタンでの戦争と2003-11年のイラク戦争が含まれました。[183] [184]

政府の手頃な価格の住宅を促進するために設計されたポリシー、[185]企業や規制ガバナンスにおける広範な障害、[186]と連邦準備制度理事会によって設定された歴史的な低金利が[187]につながった2000年代半ば住宅バブルで絶頂に達し、2008年の金融危機、大恐慌以来の国内最大の経済収縮。[188] 最初のアフリカ系アメリカ人[189]で多民族[190]の大統領であったバラクオバマが危機の最中[191]に選出され、その後刺激策に合格したそして、ドッド・フランク法は、その負の影響を緩和し、確保するための試みで、危機の繰り返しがないでしょう。2010年、オバマ政権は手頃な価格の医療法を可決しました。これにより、委任、助成金、保険取引など、約50年間で米国の医療制度に抜本的な改革が行われました。

イラクの米軍は2009年と2010年に大量に撤退し、この地域での戦争は2011年12月に正式に宣言された[192]が、数か月前に海王星スピア作戦でアルカイダの指導者が死亡した。パキスタン。[193] 2016年の大統領選挙では、共和党のドナルドトランプ氏が米国の第45代大統領に選出され、国の歴史の中で大統領に選出された最古で裕福な人物となった。[194]

2020年1月20日、米国でのCOVID-19の最初の症例が確認されました。[195]次の3か月間で、この疾患は200万人以上のアメリカ人に影響を与え、115,000人以上が死亡しました。[196]米国は、2020年6月10日の時点で、COVID-19が最も多い国である。

地理、気候、環境

48の連続した状態とコロンビア特別区は、3,119,884.69平方マイル(8,080,464.3キロの複合面積占有2)。この面積のうち、2,959,064.44平方マイル(7,663,941.7 km 2)は隣接する土地であり、米国の総土地面積の83.65%を占めています。[198] [199] ハワイは、北アメリカの南西、太平洋の中央にある群島を占めており、面積は10,931平方マイル(28,311 km 2)です。プエルトリコ、アメリカ領サモア、グアム、北マリアナ諸島、および米領バージン諸島の人口密集地域合わせて9,185平方マイル(23,789 km 2)をカバーします。[200]陸地のみで測定した米国は、ロシアおよび中国に次ぐ第3位であり、カナダに続きます。[201]

米国は、総面積(土地と水)で世界第3位または4 番目に大きい国であり、ロシアおよびカナダに次ぐランクであり、中国とほぼ同じです。ランキングは、中国とインドが係争している2つの地域をどのようにカウントするか、および米国の合計サイズをどのように測定するかによって異なります。[e] [202] [203]

海岸平野の大西洋沿岸は、内陸部への道をさらに与え落葉樹林との丘陵ピエモンテ。[204]アパラチア山から東海岸を分割五大湖との草原中西部。[205]ミシシッピ - ミズーリ川、世界最長の第四の川システムは、国の心臓を主に南北を実行します。グレートプレーンズの平らで肥沃な大草原は西に伸び、南東の高地地域。[205]

ロッキー山脈、グレートプレーンズの西部には、中に周りの14000フィート(4300メートル)をピークに達し、全国の南北に広がるコロラド州。[206]さらに西は岩が多いグレートベースンとチワワやモハベなどの砂漠です。[207]シエラネバダとカスケード山脈が近くに実行太平洋岸の両方範囲は14000フィート(4300メートル)よりも高い高度に達します。最低と最高点での連続した米国は、の状態にあるカリフォルニア、[208]距離は約84マイル(135 km)です。[209] 20310フィート(6,190.5メートル)の標高では、アラスカのデナリは国で、北米で最も高いピークです。[210]アクティブ火山はアラスカの全体に共通しているアレクサンダーとアリューシャン列島、そしてハワイは火山島で構成されています。supervolcano基礎となるイエローストーン国立公園でロッキー山脈は大陸最大の火山の機能です。[211]

そのサイズと地理的多様性が大きい米国には、ほとんどの気候タイプが含まれます。100番目の子午線の東側では、気候は北の湿った大陸から南の湿った亜熱帯までの範囲です。[212] 100番目の子午線の西にあるグレートプレーンズは半乾燥地帯です。西部の山々の多くは高山気候です。気候は乾燥グレートベースンでは、南西部の砂漠、地中海での沿岸カリフォルニア、および海洋沿岸でオレゴン州とワシントンと南アラスカ。アラスカのほとんどは亜寒帯または極地。ハワイとフロリダの南端は熱帯で、カリブ海と太平洋にその領土があります。[213]メキシコ湾に隣接する州ではハリケーンが発生しやすく、世界のほとんどの竜巻は中西部と南部のトルネードアリーエリアを中心に国内で発生しています。[214]全体として、米国は世界で最も激しい悪天候を抱えており、世界の他のどの国よりも影響力の強い極端な天候の出来事を受けています。[215]

野生生物と保護

米国の生態系は非常に多様です。隣接する米国とアラスカでは約17,000種の維管束植物が生息し、ハワイでは1,800種以上の顕花植物が見られますが、本土ではその数はわずかです。[217]アメリカ合衆国には、哺乳類428種、鳥784種、爬虫類311種、両生類295種[218]、および約91,000種の昆虫が生息しています。[219]

62の国立公園と、連邦政府が管理する他の何百もの公園、森林、荒野地域があります。[220]要するに、政府は、国の陸地面積の約28%、所有している[221]ほとんどで西部の州を。[222]この土地のほとんどは保護されていますが、一部は石油とガスの掘削、採掘、伐採、または牛の牧場にリースされており、約.86%が軍事目的で使用されています。[223] [224]

環境問題は、油との討論などが原子力エネルギーを空気や水の汚染、野生動物、伐採や保護の経済的コストを扱う、森林伐採を、[225] [226]や地球温暖化への国際応答。[227] [228]最も著名な環境庁は、1970年に大統領令によって作成された環境保護庁(EPA)です。[229]荒野の概念は、1964年以来、荒野法とともに公有地の管理に影響を与えてきました。[230]絶滅危惧種法1973年の法律は、絶滅の危機に瀕している種とその生息地を保護することを目的としており、これらは米国魚類野生生物局によって監視されています。[231]

人口統計

人口

| 歴史的人口 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 国勢調査 | ポップ。 | %± | |

| 1790 | 3,929,214 | — | |

| 1800 | 5,308,483 | 35.1% | |

| 1810 | 7,239,881 | 36.4% | |

| 1820 | 9,638,453 | 33.1% | |

| 1830 | 12,866,020 | 33.5% | |

| 1840 | 17,069,453 | 32.7% | |

| 1850 | 23,191,876 | 35.9% | |

| 1860 | 31,443,321 | 35.6% | |

| 1870 | 38,558,371 | 22.6% | |

| 1880 | 50,189,209 | 30.2% | |

| 1890 | 62,979,766 | 25.5% | |

| 1900 | 76,212,168 | 21.0% | |

| 1910 | 92,228,496 | 21.0% | |

| 1920年 | 106,021,537 | 15.0% | |

| 1930 | 123,202,624 | 16.2% | |

| 1940 | 132,164,569 | 7.3% | |

| 1950 | 151,325,798 | 14.5% | |

| 1960 | 179,323,175 | 18.5% | |

| 1970 | 203,211,926 | 13.3% | |

| 1980 | 226,545,805 | 11.5% | |

| 1990 | 248,709,873 | 9.8% | |

| 2000年 | 281,421,906 | 13.2% | |

| 2010 | 308,745,538 | 9.7% | |

| EST(東部基準時。2019 [232] | 328,239,523 | 6.3% | |

| 1610–1780人口データ。[233] 国勢調査の数字はないことに注意してください 含まれていないネイティブアメリカンを 1860年まで、[234] | |||

米国勢調査局は正式に7月1日、2019年のよう328239523であることを国の人口を推定した[232]国勢調査局は継続的に更新を提供、また米国の人口時計に基づいて50州とコロンビア特別区の最新の人口を近似します局の最新の人口統計の傾向。[235]時計によると、2020年5月23日、米国の人口は3億2,900万人を超え、19秒ごとに1人(純増)、つまり1日あたり約4,547人が追加されました。米国は、中国とインド後、世界で3番目に人口の多い国。 2018年の年齢の中央値アメリカ合衆国の人口の38.1歳でした。[236]

2018年、米国には約9000万人の移民と米国生まれの移民(第2世代アメリカ人)の子供がおり、米国全体の人口の28%を占めています。[237]米国には非常に多様な人口があります。37の祖先グループには100万人以上のメンバーがいます。[238] ドイツ系アメリカ人は最大の民族グループで(5,000万人以上)、アイルランド系アメリカ人(約3700万人)、メキシコ系アメリカ人(約3100万人)、イギリス系アメリカ人(約2800万人)がそれに続きます。[239] [240]

白人のアメリカ人(主にヨーロッパの祖先)は、人口の73.1%を占める最大の人種グループです。アフリカ系アメリカ人は、国内最大の人種的少数派であり、3番目に大きな祖先グループです。[238] アジア系アメリカ人は国の2番目に大きい人種的少数派です。アジア系アメリカ人の最大の民族グループは、中国系アメリカ人、フィリピン系アメリカ人、インド系アメリカ人です。[238]ヨーロッパの祖先を持つアメリカ最大のコミュニティはあるドイツ系アメリカ人で構成され、総人口の14%以上。 [241]2010年、米国の人口には、アメリカインディアンまたはアラスカ先住民の祖先を持つ520万人(そのような祖先のみが290万人)、ハワイまたは太平洋の先住民族の祖先を持つ120万人(50万人だけ)が含まれていました。[242]国勢調査では、2010年に5つの公式レースカテゴリのいずれかと「特定できなかった」1900万人以上の「その他のレース」をカウントし、そのうちの18.5百万人(97%)がヒスパニック系民族でした。[242]

少数民族非ヒスパニック系、非多民族とは別に、すべての個人として国勢調査局で定義された、白人は、2012年に人口の37%を構成し、[243]以下歳未満の乳児の50%以上は、少数のグループのメンバーです。[244] [245]これらのグループは、2044年までに集合的に人口の過半数を占めると予測されている。[244]

2017年、米国の外国生まれの人口のうち、約45%(2070万人)が帰化市民、27%(1230万人)が合法的永住者(市民になる資格のある多くの人々を含む)、6%(220万人)が一時的でした合法的な居住者、および23%(10.5百万)は無許可の移民でした。[246]現在米国に住んでいる移民のうち、出生国の上位5か国はメキシコ、中国、インド、フィリピン、エルサルバドルです。 2017年と2018年まで、米国は何十年もの間難民の第三国定住の主導権を握り、世界の他の地域を合わせたよりも多くの難民を受け入れました。[247] 1980年度から2017年まで、難民の55%はアジアから、27%はヨーロッパから、13%はアフリカから、そして4%はラテンアメリカから来ました。[247]

2017年のギャラップ世論調査では、成人のアメリカ人の4.5%がLGBTと特定され、女性の5.1%がLGBTと特定されたのに対し、男性の3.9%と比較されました。[248]最高の割合はコロンビア特別区(10%)からのものでしたが、最低の州はノースダコタで1.7%でした。[249]

2017年の国連レポートでは、米国は2050年までの世界の人口増加が集中する9つの国の1つになると予測されていました。[250] 2020年の米国国勢調査局の報告では、移民の割合に応じて、国の人口は2060年までに3億2000万から4億4700万の間になると予測されています。予測されるすべてのシナリオで、出生率の低下と平均余命の増加は人口の高齢化をもたらします。[251]

ヒスパニック系およびラテン系アメリカ人の人口増加は、主要な人口統計学的傾向です。ヒスパニック系の5050万人のアメリカ人[242]は、国勢調査局によって明確な「民族性」を共有していると識別されています。ヒスパニック系アメリカ人の64%はメキシコ系です。[252] 2000年から2010年の間に、国のヒスパニック系人口は43%増加しましたが、非ヒスパニック系人口はわずか4.9%増加しました。[253]

米国の年間出生率は1,000人あたり13人で、1,000人あたり5人の出生率は世界平均を下回っています。[254]その人口増加率は0.7%であり、多くの先進国よりも高いです。[255] 2017年度には、100万人以上の移民(そのほとんどが家族の再会を通じて入国した)に合法的な居住が許可されました。[256]絶対数では、外国生まれの米国居住者数は過去最高(2017年には4440万人)です。ただし、全人口に占める割合として、現在の外国生まれのシェア(全人口の13.6%)は、1890年のピーク時のシェア(全人口の14.8%)よりも低くなっています。[246]

アメリカ人の約82%が都市部(郊外を含む)に住んでいます。[203]それらの約半分は50,000以上の人口を持つ都市に住んでいます。[257] 2008年、273の法人自治体の人口は10万人を超え、9つの都市には100万人を超える人口があり、4つの都市には200万人を超えました(ニューヨーク、ロサンゼルス、シカゴ、ヒューストン)。[258] 2018年の推定では、53の大都市圏の人口が100万人を超えています。南部、南西部、および西部の多くの大都市圏は、2010年から2018年の間に大幅に成長しました。ダラスそして、ヒューストンのメトロは100万人以上増加し、ワシントンDC、マイアミ、アトランタ、フェニックスのメトロはすべて50万人以上増加しました。

言語

英語(具体的には、アメリカ英語)は、米国の事実上 の国語です。連邦レベルでは公用語はありませんが、米国の帰化要件など一部の法律では英語が標準化されています。 2010年には、5歳以上の人口の80%に当たる約2億3,000万人が家庭で英語しか話せませんでした。人口の12%が自宅でスペイン語を話し、2番目に一般的な言語となっています。スペイン語も最も広く教えられている第二言語です。[259] [260]

どちらもハワイと英語が公用語であるハワイ。[261]英語に加えて、アラスカの認識20の公式のネイティブ言語を、[262] [K]とサウスダコタは認識スー。[263]どちらも公用語はありませんが、ニューメキシコ州には、ルイジアナ州が英語とフランス語と同様に、英語とスペイン語の両方の使用を規定する法律があります。[264]カリフォルニアなどの他の州は、法廷フォームを含む特定の政府文書のスペイン語版の発行を義務付けています。[265]

いくつかの島の領土は、英語とともに母国語を公式に認めています。サモア[266]はアメリカ領サモアによって公式に認められており、チャモロ[267]はグアムの公式言語です。カロリニア人とチャモロ人の両方が北マリアナ諸島で公式に認められています。[268] スペイン語はプエルトリコの公用語であり、英語よりも広く話されています。[269]

アメリカで最も広く教えられている外国語は、幼稚園から大学の学部教育までの登録数の点で、スペイン語(約720万人の学生)、フランス語(150万人)、およびドイツ語(500,000)です。その他の一般的に教えられている言語には、ラテン語、日本語、ASL、イタリア語、中国語があります。[270] [271]アメリカ人の18%は英語と他の言語の両方を話すと主張している。[272]

| 言語 | 人口の割合 |

スピーカー数 |

英語を 上手に話す人数 |

英語をあまり上手に 話せ ない人の数 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 英語 (のみ) | 〜80% | 237,810,023 | なし | なし |

| スペイン語 (スペイン語クレオールを含むがプエルトリコの居住者を除く) |

13% | 40,489,813 | 23,899,421 | 16,590,392 |

| 中国語 (北京語と広東語を含むすべての種類) |

1.0% | 3,372,930 | 1,518,619 | 1,854,311 |

| タガログ語 (フィリピンを含む) |

0.5% | 1,701,960 | 1,159,211 | 542,749 |

| ベトナム人 | 0.4% | 1,509,993 | 634,273 | 875,720 |

| アラビア語 (すべての種類) |

0.3% | 1,231,098 | 770,882 | 460,216 |

| フランス語 (パトワとケイジャンを含む) |

0.3% | 1,216,668 | 965,584 | 251,087 |

| 韓国語 | 0.2% | 1,088,788 | 505,734 | 583,054 |

宗教

アメリカの宗教(2017)[275]

米国憲法の第1改正は、宗教の自由な行使を保証し、議会がその設立に関する法律を通過させることを禁止します。

2013年の調査では、アメリカ人の56%が、宗教は「生活において非常に重要な役割」を果たしたと述べ、他のどの西欧諸国よりもはるかに高い数字でした。[276] 2009ギャラップの世論調査では、アメリカ人の42%が毎週またはほぼ毎週教会に出席したと述べました。数字はバーモント州の最低23%からミシシッピ州の最高63%の範囲でした。[277]

2014年の調査では、米国の成人の70.6%がキリスト教徒であると認定しました。[278] プロテスタントが46.5%を占め、ローマカトリック教徒は20.8%で最大の単一宗派を形成した。[279] 2014年、米国の成人人口の5.9%が非キリスト教の宗教を主張しました。[280]これらには、ユダヤ教(1.9%)、イスラム教(0.9%)、ヒンドゥー教(0.7%)、仏教(0.7%)が含まれます。[280]調査はまた、アメリカ人の22.8%が自分を不可知論者、無神論者、または単に宗教を持たないと述べたと報告しました1990年に8.2%から-UP [279] [281] [282]もありますユニテリアンユニバー、サイエントロジスト、バハイ教、シーク教、ジャイナ教、神道、ゾロアスター教、儒教、サタニスト、道教、ドルイド、ネイティブアメリカン、Afro-はアメリカ人、伝統的なアフリカ人、ウィッカ人、グノーシス派、人道主義者、そして信仰のコミュニティ。[283] [284]

プロテスタンティズムは全アメリカ人のほぼ半分を占める、米国で最大のキリスト教の宗教団体です。バプテストは共同で15.4%でプロテスタントの最大の支部を形成し[285]、南部バプテスト条約は米国の人口の5.3%で最大の個人プロテスタント宗派です。[285]バプテストとは別に、他のプロテスタントカテゴリには、非宗派のプロテスタント、メソジスト、ペンテコステ派、不特定のプロテスタント、ルター派、長老派、会衆派、その他の改革会派が含まれます。聖公/ 聖公会、クエーカー教徒、アドベンチスト、ホーリーネス、キリスト教原理主義者、アナバプティスト、ピエティスト、その他多数。[285]

他の西洋諸国と同様に、米国は信仰心が弱まっています。宗教は30歳未満のアメリカ人の間で急速に成長しています。[286]世論調査では、組織化された宗教に対するアメリカ人の全体的な信頼は1980年代半ばから後半にかけて低下しており[287]、特に若いアメリカ人はますます無関心になっています。[280] [288] 2012年の調査では、米国の人口のプロテスタントの割合は48%に低下しており、そのため、大多数の宗教的カテゴリーとしての地位を初めて終了しました。[289] [290]宗教のないアメリカ人は子供が1.7人いるのに対し、クリスチャンは2.2人である。無関係の人は、キリスト教徒の52%と比較して、37%の結婚と結婚する可能性が低くなります。[291]

バイブル・ベルトは、内地域の非公式な用語であるアメリカ南部社会的に保守的ている福音派プロテスタントは、宗派間の文化とキリスト教の教会出席の重要な一部であり、国の平均よりも一般的に高くなっています。対照的に、ニューイングランドと米国西部では、宗教は最も重要な役割を果たしていません。[277]

家族構成

2018年現在、15歳以上のアメリカ人の52%が結婚しており、6%が未亡人、10%が離婚しており、32%は結婚したことがありませんでした。[292]現在、女性はほとんど家の外で働いており、学士号の大半を取得している。[293]

米国の10代の妊娠率は、1,000人の女性あたり26.5です。率は1991年以来57%減少しました。[294] 妊娠中絶は国中で合法です。中絶率は、現在、出生1,000人あたり241人、15〜44歳の女性1,000人あたり15人ですが、減少していますが、ほとんどの西欧諸国よりも高いままです。[295] 2013年の最初の出産時の平均年齢は26歳で、出生の41%は未婚の女性でした。[296]

2016年の合計特殊出生率は、女性1000人あたりの出生数は1820.5でした。[297] 米国での採用は一般的であり、法的な観点からは比較的簡単です(他の西側諸国と比較して)。[298] 2001年現在、127,000を超える養子縁組があり、米国は世界中の養子縁組の総数のほぼ半分を占めています。[299] 同性結婚 は全国的に合法であり、同性カップルが採用する ことは合法である。一夫多妻制は米国中で違法です[300]

米国は、ひとり親家庭で暮らす子どもの割合が世界で最も高い国です。[301]

健康

米国では、2017年の出生時の平均寿命は78.6年でした。これは、数十年にわたる継続的な増加に続いて平均余命が減少した3年目です。最近の減少は、主に25歳から64歳のグループで、主に薬物の過剰摂取と自殺率の急激な増加によるものです。国は裕福な国の中で最も高い自殺率の一つを持っています。[302] [303]平均余命はアジア人とヒスパニックの間で最も高く、黒人の間で最も低かった。[304] [305] CDCおよび国勢調査局のデータによると、自殺、アルコール、薬物の過剰摂取による死亡は、2017年に過去最高を記録しました。[306]

米国での肥満の増加と他の地域での健康状態の改善により、国の平均寿命は1987年の世界の11位から2007年の42位に低下し、2017年の時点で、日本、カナダ、オーストラリアの中で平均余命が最も低かった。イギリス、そして西ヨーロッパの7カ国。[307] [308]肥満率は過去30年間で2倍以上になり、先進国の中で最高です。[309] [310]成人人口の約3分の1が肥満で、さらに3分の1が過体重です。[311]肥満関連2 型 糖尿病は、医療専門家によって流行と見なされています。[312]

2010年には、冠動脈疾患、肺ガン、脳卒中、慢性閉塞性肺疾患、交通事故は米国で失われた人生の中で最も年間発生する低バックの痛み、うつ病、筋骨格障害、首の痛みを、そして不安は、ほとんどの年はに敗れた原因障害。最も有害な危険因子は、貧しい食生活、喫煙、肥満、高血圧、高血糖、運動不足、アルコール摂取でした。アルツハイマー病、薬物乱用、腎臓病、癌、転倒により、年齢調整された1990年の一人当たりの割合を超えて、さらに多くの命が失われました。[313]米国の10代の妊娠と妊娠中絶の割合は、他の西欧諸国、特に黒人とヒスパニックの間でかなり高くなっています。[314]

米国の医療保険は、公的および私的な取り組みの組み合わせであり、普遍的ではありません。 2017年には、人口の12.2%が健康保険に加入していませんでした。[315]無保険および保険不足のアメリカ人の主題は、主要な政治問題です。[316] [317] 2010年の初めに可決された連邦法により、保険のない人口の約半分が半減しましたが、法案とその最終的な影響については論争の的となっています。[318] [319]米国の医療制度は、一人当たりの支出とGDPの割合の両方で測定すると、他の国をはるかに上回ります。[320]同時に、米国は医療イノベーションの世界的リーダーです。[321]

教育

アメリカの公教育は州政府と地方自治体によって運営されており、連邦政府の助成金に関する制限を通じて米国教育省によって規制されています。ほとんどの州では、子供は6歳または7歳(通常は幼稚園または1年生)から18歳(通常は高校の終わりに12年生に通う)まで学校に通う必要があります。一部の州では、生徒が16歳または17歳で退学することを許可しています。[322]

子どもの約12%は、教区または非宗派の 私立学校に在籍しています。子どものわずか2%がホームスクーリングです。[323]米国は、世界のどの国よりも生徒1人あたりの教育に多く費やしており、2010年の小学生1名あたり11,000ドル以上、高校生1名あたり12,000ドル以上を費やしています。[324]米国の大学生の約80%が公立大学に通っています。[325]

25歳以上のアメリカ人のうち、84.6%が高校を卒業し、52.6%が大学に進学し、27.2%が学士号を取得し、9.6%が大学院学位を取得しています。[326]基本的な識字率は約99%です。[203] [327]国連は、米国に0.97の教育指数を割り当て、世界で12番目に結び付けています。[328]

米国には高等教育の私立および公立の多くの機関があります。さまざまなランク付け組織によってリストされているように、世界のトップの大学の大部分は米国にあります[329] [330] [331]また、一般によりオープンな入学ポリシー、より短いアカデミックプログラム、およびより低い学費を持つ地域コミュニティカレッジもあります。

2018年、研究集約型の大学のネットワークであるU21は、高等教育の幅広さと質の高さで米国を世界で最初にランク付けし、GDPが要因となった15位でした。[332]高等教育への公共支出については、米国は他のいくつかのOECD諸国を下回っていますが、学生あたりの支出はOECD平均よりも多く、すべての国よりも公共および民間の支出に多くを費やしています。[324] [333] 2018年現在、学生ローンの債務は 1.5兆ドルを超えています。[334] [335]

政府と政治

アメリカ合衆国は、50州の連邦共和国、連邦区、5つの地域、およびいくつかの無人島の所有物です。[336] [337] [338]世界で最も古い現存する連盟です。それは、連邦共和国と代表的な民主主義であり、「多数の支配は法律で保護された少数派の権利によって和らげられている」。[339] 2018年、米国は民主主義指数で 25位にランクされました。[340]でトランスペアレンシー・インターナショナルの2019腐敗認識指数の公共部門 2019に69 2015年76のスコアから低下位置[341]

でアメリカの連邦制度、市民は通常の対象となる政府の三つのレベル連邦、州、および地方:。地方政府の義務は一般の間で分割されている県と市町村。ほとんどすべての場合において、行政および立法当局は、地区による市民の複数投票により選出されます。

政府は、国の最高の法的文書として機能する米国憲法によって定義されたチェックとバランスのシステムによって規制されています。[342]憲法の原文は、連邦政府の構造と責任、および個々の州との関係を確立している。第1条は、海綿体の「大物」に対する権利を保護します。憲法は27回改正されました。[343]権利章典を構成する最初の10の改正と14の改正は、アメリカ人の個人の権利の中心的な基盤を形成します。すべての法律と政府の手続きは司法審査の対象となりますそして、憲法に違反していると裁判所が決定した法律は無効になります。憲法で明示的に言及されていない司法審査の原則は、最高裁判所によってマーバリー対マディソン(1803)[344]裁判長のジョンマーシャルによって伝えられた決定で確立されました。[345]

連邦政府は3つの支部で構成されています。

- 立法:二院制 議会で構成、上院と下院は、作る連邦法を、戦争を宣言し、条約を承認し、持っている財布のパワーを、[346]との力がある弾劾を、それが座って削除することができたことで、政府のメンバー。[347]

- 大統領:大統領は軍の最高司令官であり、法律になる前に議会の法案を拒否することができ(議会の上書きが適用される)、内閣のメンバー(上院の承認が適用される)と他の役員を指名し、管理し、連邦法および政策を施行する。[348]

- 司法:最高裁判所および下級連邦裁判所は、上院の承認を得て大統領によって任命され、法律を解釈し、違憲と判断したものを覆します。[349]

下院には435人の議員がおり、それぞれ2年間の議会地区を代表しています。下院議席は、人口によって州に配分されます。次に、各州は国勢調査の配分に準拠するために単一メンバーの地区を描画します。コロンビア特別区と5つの主要な米国の領土それぞれが持っている議会の一員 -これらのメンバーが投票に許可されていません。[350]

上院は、各状態が選出された2人の上院議員、持つ100人のメンバーを持っている時に、大 6年の任期にします。上院議席の3分の1が2年ごとに選挙に出されます。コロンビア特別区と5つの主要な米国領には上院議員はいません。[350]大統領は4年間の任期を務め、選挙で選出されるのは2回までである。大統領は直接投票では選出されませんが、決定的な投票が州とコロンビア特別区に割り当てられる間接的な選挙大学システムによって選出されます。[351]最高裁判所、率いるアメリカ合衆国最高裁判所長官、生活のために仕える9人のメンバーを持っています。[352]

ネブラスカには一院制の立法府がありますが、州政府はほぼ同じように構成されています。[353]各州の知事(最高責任者)が直接選出される。一部の州の裁判官と内閣府はそれぞれの州の知事により任命され、他の人は一般投票により選出されます。

政治部門

50州は国の主要な管理部門です。これらは、郡または郡の同等物に細分され、さらに自治体に分割されます。コロンビア特別区は、アメリカ合衆国の首都ワシントンDCを含む連邦区です。[354]州とコロンビア特別区は、アメリカ合衆国の大統領を選択します。各州には、議会の代表者と上院議員の数に等しい大統領選挙人がいます。コロンビア特別区には3つあります(改正23号により)。[355] プエルトリコなどのアメリカ合衆国の領土には大統領選挙人がいないため、それらの領土の人々は大統領に投票できません。[350]

米国も、州の主権と同様に、アメリカインディアン諸国の部族主権をある程度観察しています。アメリカインディアンは米国市民であり、部族の土地は米国議会および連邦裁判所の管轄下にあります。州と同様に、彼らはかなりの自治権を持っていますが、州と同様に、部族は戦争をしたり、自分の外交関係に従事したり、通貨を印刷して発行したりすることはできません。[356]

市民権は、すべての州、コロンビア特別区、およびアメリカ領サモアを除くすべての主要な米国領で出生時に付与されます。[357] [358] [m]

政党と選挙

45 代目の大統領

48代目の副大統領

米国は、その歴史の大部分で2党制で運営されてきました。[361]ほとんどのレベルの選挙区では、州が管理する予備選挙が、その後の総選挙のために主要党の候補者を選ぶ。以来1856年の総選挙、主要政党はされている民主党、1824年に設立され、共和党、1854年に設立されました。南北戦争以来、唯一のサードパーティの大統領候補、元大統領セオドア・ルーズベルトは、として実行されているプログレッシブで1912年-人気投票の20%を獲得しました。社長と副社長は、によって選出されている選挙人団。[362]

アメリカの政治文化では、右中央の共和党は「保守的」と見なされ、左中央の民主党は「自由主義」と見なされます。[363] [364]の状態東北と西海岸ととして知られている五大湖の状態、いくつかの「青の状態は、」比較的リベラルです。南部のグレートプレーンズとロッキー山脈の「赤い州」は比較的保守的です。

2016年の大統領選挙で優勝した共和党のドナルドトランプ氏が米国の第45 代大統領を務めています。[365]上院でのリーダーシップには、共和党のマイクペンス副大統領、共和党の臨時大統領チャックグラスリー、多数党首ミッチマコーネル、および少数党首チャックシューマーが含まれる。[366]ハウスでのリーダーシップは、下院議長が含まナンシー・ペロシ、院内総務ステニー・ホイヤー、そして少数リーダーのケビン・マッカーシーを。[367]

で第116米国議会、下院は民主党によって制御され、上院は共和党によって制御され、米国のスプリット議会を与えます。上院は、53人の共和党員と45人の民主党員で構成され、2人の無所属議員が民主党員と因果関係を結んでいます。下院は233人の民主党員、196人の共和党員、1人の自由党員で構成されています。[368]州知事のうち26人の共和党員と24人の民主党員がいる。 DC市長と5人の準州知事の間には、2人の共和党員、1人の民主党員、1人の新進歩党員、2人の無所属議員がいます。[369]

外交関係

米国には外交関係の確立された構造があります。国連安全保障理事会の常任理事国です。ニューヨーク市には国連本部があります。ワシントンDCにはほとんどすべての国に大使館があり、多くの国に領事館があります。同様に、ほぼすべての国がアメリカの外交使節団を主催しています。ただし、イラン、北朝鮮、ブータン、および中華民国(台湾)は、米国と正式な外交関係を結んでいません(米国は依然としてブータンおよび台湾と非公式の関係を維持しています)。[370]G7、[371] G20、OECDのメンバーです。

米国は英国と「特別な関係」を持ち[372]、インド、カナダ、[373]オーストラリア、[374]ニュージーランド、[375]フィリピン、[376]日本、[377]南と強いつながりがあります韓国、[378]イスラエル、[379]、およびフランス、イタリア、ドイツ、スペイン、ポーランドを含むいくつかの欧州連合諸国。 [380]軍事問題や安全保障問題について NATOメンバーと緊密に連携し、アメリカ国家機構やカナダおよびメキシコとの三国間北米自由貿易協定などの自由貿易協定を通じて、近隣諸国と緊密に連携しています。コロンビアは伝統的に南米で最も忠実な同盟国として米国によって考えられています。[381] [382]

米国は、自由連合のコンパクトを通じて、ミクロネシア、マーシャル諸島、パラオに対する完全な国際防衛当局および責任を行使します。[383]

政府財政

米国の課税は、連邦、州、および地方政府のレベルで課されます。これには、収入、給与、財産、販売、輸入、地所、贈り物、およびさまざまな手数料に対する税金が含まれます。米国の課税は居住地ではなく市民権に基づいています。[384]非居住者の市民と海外に住むグリーンカードの所有者はどちらも、どこに住んでいるか、どこで収入を得ているかに関係なく、所得に課税されます。米国は、世界でこれを行う唯一の国です。[385]

2010年に連邦、州、地方自治体が徴収した税金はGDPの 24.8%に達しました。[386] CBOの見積もりに基づいて、[387] 2013年の税法では、上位1%が1979年以来の平均税率が最も高く、他の所得グループは歴史的な低水準のままです。[388] 2018年の最も裕福な400世帯の実効税率は23%でしたが、米国の世帯の下半分は24.2%でした。[389]

2012会計年度の間に、連邦政府は予算または現金ベースで3.54兆ドルを費やしました。これは、2011会計年度の費用である3.5兆ドルに対して600億ドルまたは1.7%減少したものです。2012会計年度の支出の主なカテゴリには、メディケアとメディケイド(23%)、社会保障(22%)、国防総省(19%)、非防御裁量(17%)、その他の必須(13%)および利息(6 %)。[391]

米国における米国の総国家債務は 2014年に18.527兆ドル(GDPの106%)でした。[392] [n]米国は世界最大の対外債務[396]と34番目に大きい政府を抱えています世界のGDPの%としての債務。[397]

ミリタリー

社長は、最高司令官の国の軍隊とその指導者を任命、国防長官と統合参謀本部。米国国防総省は含む武装勢力、管理して陸軍、海兵隊、海軍、空軍、およびスペースフォース。沿岸警備隊はによって運営されている国土安全保障省平時におけるとで海軍省戦争の時代に。 2008年、軍には140万人の現役職員がいた。の国家警備隊兵士の総数を230万人に予備し、もたらした。国防総省はまた、請負業者を含まない約70万人の民間人を雇用した。[398]

兵役は自発的ですが、戦争中は選択的兵役制度により徴兵が発生する可能性があります。[399]アメリカ軍は、空軍の大型輸送機、海軍の11の空母、および海軍の大西洋と太平洋の艦隊と海上にいる海兵隊遠征隊によって急速に配備することができます。軍は海外に865の基地と施設[400]を運営しており、25か国で100人を超える現役職員を配備しています。[401]

2011年の米国の軍事予算は 7,000億ドルを超え、世界の軍事支出の41%でした。 GDPの4.7%で、サウジアラビアに次いで、上位15の軍事支出者の中で2番目に高い率でした。[402] 国防費は科学技術投資において主要な役割を果たしており、米国連邦研究開発の約半分は国防総省によって資金提供されています。[403]米国経済全体における国防の割合は、ここ数十年で概して低下しており、冷戦のピークは1953年のGDPの14.2%、1954年の連邦支出の69.5%、2011年のGDPの4.7%、18.8%でした。[404]

国は5つの承認された 核兵器国の1つであり、世界で 2番目に大きい核兵器の備蓄を保有しています。[405]世界の14,000核兵器の90%以上がロシアと米国によって所有されています。[406]

法執行機関と犯罪

米国の法執行機関は、州の警察がより広範なサービスを提供するとともに、主に地元の警察署と保安官事務所の責任です。連邦捜査局(FBI)やUS Marshals Serviceなどの連邦政府機関には、公民権の保護、国家安全保障、米国連邦裁判所の判決や連邦法の施行などの特別な義務があります。[407]州裁判所はほとんどの刑事裁判を行い、連邦裁判所は特定の指定された犯罪および州刑事裁判所からの特定の控訴を処理します。

2010年 の世界保健機関の死亡率データベースの断面分析は、米国が「銃による殺人率が25.2倍高かったため、他の高所得国よりも殺人率が7.0倍高かった」ことを示しました。[408] 2016年、米国の殺人率は10万人あたり5.4でした。[409]憲法修正第2条によって保証される銃の所有権は、引き続き争議の主題である。

米国は、文書化された投獄率が最も高く、刑務所の人口は世界で最大です。[410] 2020年の時点で、刑務所政策イニシアチブは約230万人が投獄されたと報告した。[411]は 州または連邦の施設内の複数年を言い渡され、すべての囚人のために投獄率は2013年10万人あたりの478である[412]によると、刑務所の連邦局、連邦刑務所で開催された受刑者の大半は、薬物の有罪判決を受けています犯罪。[413]囚人の約9%が民営化された刑務所に収容されている。[411]私営刑務所の実務は1980年代に始まり、論争の的となってきた。[414]

米国では特定の連邦犯罪および軍事犯罪、さらに30州の州レベルで死刑が制裁されています。[415] [416] 1967年から1977年にかけて死刑の恣意的な賦課を取り消した米国最高裁判所の判決により、処刑は行われなかった。判決以来、1,300件以上の死刑が執行されており、これらの過半数はテキサス州、バージニア州、オクラホマ州の3つの州で行われています。[417]その間、いくつかの州は死刑法を廃止または廃止した。 2019年、国は中国、イラン、サウジアラビアに続き、世界で6番目に高い死刑執行件数を記録しました。イラク、エジプト。[418]

経済

| 経済指標 | ||

|---|---|---|

| 名目GDP | 20.66兆ドル(2018年第3四半期) | [419] |

| 実質GDP成長率 | 3.5%(2018年第3四半期) | [419] |

| 2.1%(2017) | [419] | |

| CPIインフレ | 2.2%(2018年11月) | [420] |

| 雇用と人口の比率 | 60.6%(2018年11月) | [421] |

| 失業 | 3.7%(2018年11月) | [422] |

| 労働力率 | 62.9%(2018年11月) | [423] |

| 公債総額 | 21.85兆ドル(2018年11月) | [424] |

| 世帯純資産 | 109.0兆ドル(2018年第3四半期) | [425] |

国際通貨基金によれば、16.8兆ドルの米国GDPは、市場為替レートでの世界の総生産の 24%、購買力平価(PPP)での世界の総生産の19%を超えます。[426]米国は商品の最大の輸入国であり、2番目に大きい輸出国ですが、一人当たりの輸出は比較的低いです。2010年の米国の貿易赤字総額は6,350億ドルでした。[427] カナダ、中国、メキシコ、日本、ドイツは、その最大の貿易相手国です。[428]

1983年から2008年まで、米国の実質複利年次GDP成長率は3.3%でしたが、それ以外のG7の加重平均は2.3%でした。[429]国は一人当たり名目GDP [430]で世界で9位、PPPで一人当たりGDPで6 位にランクされています。[426]米ドルは世界の一次で準備通貨。[431]

2009年、民間部門は経済の86.4%を構成すると推定されました。[434]その経済はポスト産業レベルの発展に達しているが、米国は依然として産業大国である。[435] 2015年の米国経済の68%は個人消費でした。[436] 2010年8月のアメリカの労働力は1億5,410万人(50%)でした。 2,120万人を擁する政府は、主要な雇用分野です。最大の民間雇用部門は、医療と社会扶助であり、1640万人がいます。それは小さく、福祉国家を、ほとんどのヨーロッパ諸国よりも政府の行動を通じて以下の所得を再分配します。[437]

米国は、労働者の有給休暇を保証しない唯一の先進国であり[438]、法的権利として有給の家族休暇がない世界でも数少ない国の1つです。[439]連邦法は病気休暇を要求していませんが、公務員や企業の正社員にとって共通の利益です。[440]フルタイムのアメリカの労働者の74%はによると、病気休暇を支払わ労働統計局パートタイム労働者のわずか24%が同じ利益を得るが、。[440] 2009年、米国はルクセンブルグに次ぐ、世界で3番目に高い労働力生産性を誇っていますとノルウェー。両国とオランダに次ぐ、1時間あたりの生産性は4番目でした。[441]

科学技術

米国は19世紀後半から技術革新、20世紀半ばから科学研究をリードしてきました。交換可能な部品の製造方法は、19世紀前半に連邦軍によって米軍省によって開発されました。この技術は工作機械産業の確立とともに、19世紀後半に米国でミシンや自転車などの大規模な製造を可能にし、アメリカの製造システムとして知られるようになりました。20世紀初頭の工場の電化と組立ラインの導入、その他の省力化技術により、大量生産。[442]21世紀の研究開発資金の約3分の2は、民間部門からのものです。[443]米国は科学研究論文とインパクトファクターで世界をリードしています。[444] [445]

1876年、アレクサンダーグラハムベルは米国で最初の電話特許を取得しました。初めてのトーマス・エジソンの研究所は、蓄音機、最初の長寿命の電球、そして最初の実用的な映画用カメラを開発しました。[446]全世界の出現につながった後者のエンターテインメント業界。 20世紀初頭、ランサムE.オールズとヘンリーフォードの自動車会社が組立ラインを普及させました。ライト兄弟は、1903年に、作られました最初の持続的かつ制御された空中重動力飛行。[447]

1920年代と30年代のファシズムとナチズムの台頭により、アルバートアインシュタイン、エンリコフェルミ、ジョンフォンノイマンなどの多くのヨーロッパの科学者が米国に移住するようになりました。[448]第二次世界大戦中、マンハッタン計画は核兵器を開発し、原子時代を先導しました。一方、宇宙競争はロケット工学、材料科学、および航空学において急速な進歩をもたらしました。[449] [450]

1950年代のトランジスタの発明は、事実上すべての現代の電子機器の主要なアクティブコンポーネントであり、多くの技術開発と米国の技術産業の大幅な拡大をもたらしました。[451]これは、順番に、など、全国の多くの新技術企業と地域の設立につながったシリコンバレーカリフォルニアインチアメリカによって進歩マイクロプロセッサのような会社アドバンスト・マイクロ・デバイス(AMD)、およびIntelのコンピュータの両方と一緒にソフトウェアやハードウェアなどが企業アドビシステムズ、アップル社を、IBM、Microsoft、およびSun Microsystemsは、パーソナルコンピュータを作成して普及させました。ARPANETは、満たすために1960年代に開発された国防総省の要件、およびの最初になった進化一連のネットワークにインターネット。[452]

所得、貧困、富

世界人口の 4.24%を占めるアメリカ人は、世界の総資産の29.4%を集合的に所有しており、アメリカ人は世界の億万長者の人口のおよそ半分を占めています。[453]世界の食料安全保障指数は 2013年3月に食品手頃な価格と全体的な食料安全保障のための米国のナンバーワンにランク[454]アメリカ人、平均では、複数回として住居と一人あたりにつき多くの生活空間として持っている欧州連合の住民、そしてよりすべてのEU諸国より。[455] 2017年、国連開発計画は、人間開発指数で189か国中、米国を13位にランク付けしました不平等調整済みHDI(IHDI)の151か国中25位。[456]

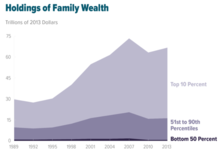

富は、所得や税金と同様に、非常に集中しています。成人人口の最も裕福な10%は国の家計資産の72%を所有していますが、下半分は2%しか主張していません。[457]連邦準備制度による2017年9月のレポートによると、2016年の上位1%は国の富の38.6%を支配していました。[458] OECDによる2018年の調査によると、他のほぼすべての先進国よりも所得労働者。これは主に、リスクのある労働者が政府の支援をほとんど受けておらず、非常に弱い団体交渉システムによってさらに後退しているためです。[459]所得者上位1%2009年から2015年までの所得増加の52%を占めており、所得は政府移転を除く市場所得として定義されています。[460] 2018年、米国の所得格差は国勢調査局が記録した最高レベルに達しました。[461]

何年も停滞した後、家計収入の中央値は2年間連続で過去最高の成長を記録した後、2016年に過去最高に達しました。しかし、所得格差は過去最高を維持しており、所得の上位5分の1が全所得の半分以上を占めています。[463]上位1%が受け取った総年収のシェアの上昇は、1976年の9%から2011年の20%へと2倍以上に増加し、所得格差に大きな影響を与えており[464]、 OECD諸国間で最も広い所得分配の。[465] 所得の不平等の程度と関連性については議論の余地がある。[466] [467] [468]

2007年6月から2008年11月の間に、世界的な不況は世界中で資産価格の下落をもたらしました。アメリカ人が所有する資産は、その価値の約4分の1を失いました。[469] 2007年の第2四半期にピークに達して以来、家計資産は14兆ドル減少しましたが、2006年の水準を超えて14兆ドル増加しています。[470] 2014年末の家計債務は11.8兆ドルになり[471]、2008年末の13.8兆ドルから減少した[472]

2014年1月の合衆国では、約578,424人のシェルター付きおよびシェルターなしのホームレスの人々がおり、 3分の2近くが緊急シェルターまたは暫定住宅プログラムに滞在しています。[473] 2011年には、1670万人の子供たちが食料不安な世帯に住んでおり、2007年のレベルより約35%多いですが、米国の子供たちのわずか1.1%、つまり845,000人だけが、年間のある時点で食物摂取量の減少や食事パターンの混乱を経験しました。そしてほとんどの場合は慢性ではなかった。[474] 2018年6月の時点で、米国の人口のおよそ12.7%である4,000万人が貧困状態にあり、18.5百万人が深刻な貧困状態(貧困のしきい値の半分未満の家族所得)と5歳以上万人が「第三世界で」「条件」2016年には、1,330万人の子供が貧困の中で生活しており、貧困人口の32.6%を占めていました。[475] 2017年、米国の州または準州で最も貧困率が低いのは、ニューハンプシャー(7.6%)でした。最も高いのはアメリカ領サモア(65%)であった[476] [477] [478]

インフラ

交通手段

個人輸送は、400万マイル(640万キロ)の公道のネットワーク上で動作する自動車が主流です。[480]米国は世界で2番目に大きい自動車市場[481]を持ち、1人あたりの自動車所有率は世界で最も高く、1,000人のアメリカ人あたり765台です(1996)。[482] 2017年には、255,009,283台の非二輪自動車があり、1,000人あたり約910台でした。[483]

市民の航空業界は完全に個人的に所有されており、主にされた1978年以降規制緩和ながら、ほとんどの主要空港が公に所有されています。[484]運ばれた乗客によって世界で3つの最大の航空会社は米国ベースです。アメリカン航空は、2013年にUSエアウェイズに買収された後のナンバーワンです。[485]世界で最も忙しい50の旅客空港のうち、16はアメリカ合衆国にあり、最も忙しいのはハーツフィールドジャクソンアトランタ国際空港です。[486]

エネルギー

米国のエネルギー市場は29,000程度であるテラワット時間年間。[487] 2005年、このエネルギーの40%は石油、23%は石炭、22%は天然ガスによるものです。残りは原子力および再生可能エネルギー源によって供給された。[488]

2007年以降、米国による温室効果ガスの総排出量は国で2番目に多く、中国だけが超えています。[489]米国は歴史的に世界最大の温室効果ガス生産国であり、一人当たりの温室効果ガス排出量は依然として高いままです。[490]

文化

米国には多くの文化と多種多様な民族、伝統、価値観があります。[492] [493]はさておきからネイティブアメリカン、ハワイ先住民、およびネイティブアラスカ集団、ほぼすべてのアメリカ人や彼らの祖先が定住したり、過去5世紀以内に移住しました。[494]主流のアメリカ文化は、主にヨーロッパからの移民の伝統に由来する西洋の文化であり、アフリカの奴隷によってもたらされた伝統など、他の多くの情報源からの影響を受けています。[492] [495]最近のアジアからの移民特にラテンアメリカは、均質化するるつぼと、移民とその子孫が独特の文化的特徴を保持する不均一なサラダボウルの両方として説明されている文化的ミックスに加わっています。[492]

アメリカ人は伝統的に強いによって特徴づけられている仕事の倫理、競争力、そして個人主義[496]と同様に「で統一信念アメリカの信条の自由、平等、私有財産、民主主義、法の支配、および限定されたの優先を強調します」政府。[497]アメリカ人は世界基準で非常に慈善活動をしています。 2006年のイギリスの調査によると、アメリカ人は他のどの国よりも多くのGDPの1.67%を慈善団体に寄付しました。[498] [499] [500]

アメリカン・ドリーム、またはアメリカ人は高い楽しむという認識社会移動は、移民を誘致する上で重要な役割を果たしています。[501]この認識が正確かどうかは議論の的となってきました。[502] [503] [504] [505] [429] [506]主流の文化では米国は階級のない社会であるとされていますが、[507]学者は国の社会階級間の大きな違いを特定し、社会化、言語、値。[508]アメリカ人は社会経済的成果を大いに重視する傾向がありますが、普通または平均的ですまた、一般的に肯定的な属性と見なされます。[509]

文学、哲学、視覚芸術

18世紀から19世紀初頭にかけて、アメリカの芸術と文学はその手がかりのほとんどをヨーロッパから取り入れました。ワシントンアーヴィング、ナサニエルホーソーン、エドガーアランポー、ヘンリーデビッドソローなどの作家は、19世紀半ばまでに独特のアメリカ文学の声を確立しました。マークトウェインと詩人ウォルトホイットマンは、世紀の後半の主要人物でした。エミリーディキンソンは生涯ほとんど知られていないが、今や不可欠なアメリカ人詩人として認められている。[510]ハーマンメルビルの『モビーディック』など、国の経験と性格の基本的な側面を捉えた作品(1851)、ハックルベリーフィンの冒険(1885)、F。スコットフィッツジェラルドのグレートギャツビー(1925)、ハーパーリーのモッキンバードを殺す(1960)—「グレートアメリカンノベル」と呼ばれることもあります。[511]

12人の米国市民がノーベル文学賞を受賞しました。最近では2016年にボブディランが受賞しました。ウィリアムフォークナー、アーネストヘミングウェイ、ジョンスタインベックは、20世紀で最も影響力のある作家にしばしば指名されています。[512]アメリカで発達した西洋やハードボイルドフィクションなどの人気の文学ジャンル。ビート世代の作家が持っているとして、新しい文学的なアプローチを開いたポストモダンのような作家ジョン・バース、トマス・ピンチョン、そしてドン・デリーロを。[513]

超越ソローとが率いる、ラルフ・ワルド・エマーソンは、最初の主要な設立のアメリカ哲学的な運動を。南北戦争後、チャールズサンダースパース、そしてウィリアムジェームズとジョンデューイが実用主義の発展のリーダーになりました。20世紀、WVO QuineとRichard Rorty、そして後にNoam Chomskyの業績は、分析哲学をアメリカの哲学研究者の前にもたらしました。ジョン・ロールズとロバート・ノジックも政治哲学の復活を導いた。

視覚芸術では、ハドソンリバースクールはヨーロッパの自然主義の伝統における19世紀半ばの運動でした。 1913年にニューヨーク市で開催されたアーモリーショーは、ヨーロッパのモダニズムアートの展示であり、国民に衝撃を与え、アメリカのアートシーンを一変させました。[514] ジョージア・オキーフ、マースデン・ハートレー、その他は、新しい個性的なスタイルを試しました。などの主要な芸術的な動き抽象表現のジャクソン・ポロックとウィレム・デ・クーニングとポップアートのアンディ・ウォーホルやロイ・リキテンスタイン主に米国で開発されました。モダニズム、そしてポストモダニズムの潮流は、フランクロイドライト、フィリップジョンソン、フランクゲーリーなどのアメリカの建築家に名声をもたらしました。[515]アメリカ人は長い間、現代の芸術的な写真の媒体において重要であり、アルフレッドスティーグリッツ、エドワードシュタイヘン、エドワードウェストン、アンセルアダムスなどの主要な写真家がいました。[516]

食物

主流のアメリカ料理は他の西洋諸国のものと似ています。小麦は小麦粉で作られた穀物製品の四分の三程度で主要穀物である[517]と多くの料理がで消費された、このような七面鳥、鹿肉、ジャガイモ、サツマイモ、トウモロコシ、カボチャ、とメープルシロップなど先住民食材を使用しますネイティブアメリカンと初期ヨーロッパの開拓者。[518]これらの自家製食品は、アメリカで最も人気のある休日の1つである感謝祭の共有全国メニューの一部です。[519]

世界最大のアメリカのファーストフード産業[520]は、1940年代にドライブスルー形式を開拓しました。[521]アップルパイ、フライドチキン、ピザ、ハンバーガー、ホットドッグなどの特徴的な料理は、さまざまな移民のレシピに基づいています。フライドポテト、ブリトーやタコスなどのメキシコ料理、イタリアの食材を自由に取り入れたパスタ料理は広く消費されています。[522]アメリカ人はお茶の3倍のコーヒーを飲みます。[523]米国産業界によるマーケティングは、オレンジジュースや牛乳のユビキタスな朝食用飲料の製造に大きく関与しています。[524] [525]

音楽

少しの時間で知られているが、チャールズ・アイヴスのような実験研究しながら、1910年代の作品は、古典の伝統に最初の主要な米国の作曲家として彼を設立ヘンリー・カウエルとジョン・ケージは、古典的な構成に特徴的なアメリカのアプローチを作成しました。アーロンコプランドとジョージガーシュウィンは、ポピュラー音楽とクラシック音楽の新しい統合を開発しました。

アフリカ系アメリカ人の音楽のリズミカルで叙情的なスタイルは、ヨーロッパやアフリカの伝統とは異なり、アメリカの音楽全般に深く影響を与えてきました。ブルースなどの民俗イディオムや現在は古くから知られている音楽などの要素が採用され、世界中の聴衆に人気のあるジャンルに変身しました。ジャズは、20世紀初頭にルイアームストロングやデュークエリントンなどのイノベーターによって開発されました。1920年代に発展したカントリーミュージック、1940年代にリズムとブルース。[526]

エルビスプレスリーとチャックベリーは、1950年代半ばのロックンロールのパイオニアの1人でした。メタリカ、イーグルス、エアロスミスなどのロックバンドは、世界で最も高い売上を記録しています。[527] [528] [529] 1960年代、ボブディランはフォークリバイバルから抜け出し、アメリカで最も有名なソングライターの1人となり、ジェームスブラウンはファンクの開発を主導しました。

最近のアメリカの作品には、ヒップホップやハウスミュージックが含まれています。エルビスプレスリー、マイケルジャクソン、マドンナなどのアメリカのポップスターは、テイラースウィフト、ブリトニースピアーズ、ケイティペリー、ビヨンセ、ジェイZ、エミネム、カニエウェスト、アリアナなどの現代音楽アーティストと同様に、世界的なセレブになった[526]。グランデ。[530]

シネマ

カリフォルニア州ロサンゼルスの北部地区であるハリウッドは、映画制作のリーダーの1人です。[531]世界初の商業映画展は、トーマスエジソンのキネトスコープを使用して、1894年にニューヨーク市で開催されました。[532] 20世紀初頭以来、米国の映画産業はハリウッドとその周辺に主に拠点を置いてきましたが、21世紀には映画が作られず、映画会社はグローバリゼーションの影響を受けました。[533]

ディレクターDWグリフィス、トップのアメリカ映画監督の間に無声映画の時代は、開発の中心だった映画の文法、およびプロデューサー/起業家ウォルト・ディズニーは、両方のリーダーだったアニメーション映画と映画のマーチャンダイジング。[534]ジョンフォードなどの監督はアメリカの旧西部のイメージを再定義し、ジョンヒューストンなどの他の監督と同様に、ロケ撮影で映画の可能性を広げました。 「ハリウッドの黄金時代」と一般的に呼ばれている業界では、黄金期を楽しんでいました」、サウンドの初期から1960年代初頭まで[535]、ジョンウェインやマリリンモンローなどのスクリーン俳優が象徴的な人物になりました。[536] [537] 1970年代には、「ニューハリウッド」または「ハリウッドルネサンス」[ 538]は、戦後のフランスとイタリアの写実主義の写真に影響を受けたグリティエ映画によって定義された[539]最近では、スティーブンスピルバーグ、ジョージルーカス、ジェームズキャメロンなどの監督が、彼らの大ヒット映画で有名になり、高い生産コストと収益により、Russo brothers' Avengers: Endgame (2019) being the highest-grossing film of all time.[540]

Notable films topping the American Film Institute's AFI 100 list include Orson Welles's Citizen Kane (1941), which is frequently cited as the greatest film of all time,[541][542] Casablanca (1942), The Godfather (1972), Gone with the Wind (1939), Lawrence of Arabia (1962), The Wizard of Oz (1939), The Graduate (1967), On the Waterfront (1954), Schindler's List (1993), Singin' in the Rain (1952), It's a Wonderful Life (1946) and Sunset Boulevard (1950).[543] The Academy Awards, popularly known as the Oscars, have been held annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences since 1929,[544] and the Golden Globe Awards have been held annually since January 1944.[545]

Sports

American football is by several measures the most popular spectator sport;[547] the National Football League (NFL) has the highest average attendance of any sports league in the world, and the Super Bowl is watched by tens of millions globally. Baseball has been regarded as the U.S. national sport since the late 19th century, with Major League Baseball (MLB) being the top league. Basketball and ice hockey are the country's next two leading professional team sports, with the top leagues being the National Basketball Association (NBA) and the National Hockey League (NHL). College football and basketball attract large audiences.[548] In soccer, the country hosted the 1994 FIFA World Cup, the men's national soccer team qualified for ten World Cups and the women's team has won the FIFA Women's World Cup four times; Major League Soccer is the sport's highest league in the United States (featuring 23 American and three Canadian teams). The market for professional sports in the United States is roughly $69 billion, roughly 50% larger than that of all of Europe, the Middle East, and Africa combined.[549]

Eight Olympic Games have taken place in the United States. The 1904 Summer Olympics in St. Louis, Missouri were the first ever Olympic Games held outside of Europe.[550] As of 2017, the United States has won 2,522 medals at the Summer Olympic Games, more than any other country, and 305 in the Winter Olympic Games, the second most behind Norway.[551] While most major U.S. sports such as baseball and American football have evolved out of European practices, basketball, volleyball, skateboarding, and snowboarding are American inventions, some of which have become popular worldwide. Lacrosse and surfing arose from Native American and Native Hawaiian activities that predate Western contact.[552] The most watched individual sports are golf and auto racing, particularly NASCAR.[553][554]

Mass media

The four major broadcasters in the U.S. are the National Broadcasting Company (NBC), Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), American Broadcasting Company (ABC), and Fox Broadcasting Company (FOX). The four major broadcast television networks are all commercial entities. Cable television offers hundreds of channels catering to a variety of niches.[555] Americans listen to radio programming, also largely commercial, on average just over two-and-a-half hours a day.[556]

In 1998, the number of U.S. commercial radio stations had grown to 4,793 AM stations and 5,662 FM stations. In addition, there are 1,460 public radio stations. Most of these stations are run by universities and public authorities for educational purposes and are financed by public or private funds, subscriptions, and corporate underwriting. Much public-radio broadcasting is supplied by NPR. NPR was incorporated in February 1970 under the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967; its television counterpart, PBS, was created by the same legislation. As of September 30, 2014, there are 15,433 licensed full-power radio stations in the U.S. according to the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC).[557]

Well-known newspapers include The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and USA Today.[558] Although the cost of publishing has increased over the years, the price of newspapers has generally remained low, forcing newspapers to rely more on advertising revenue and on articles provided by a major wire service, such as the Associated Press or Reuters, for their national and world coverage. With very few exceptions, all the newspapers in the U.S. are privately owned, either by large chains such as Gannett or McClatchy, which own dozens or even hundreds of newspapers; by small chains that own a handful of papers; or in a situation that is increasingly rare, by individuals or families. Major cities often have "alternative weeklies" to complement the mainstream daily papers, such as New York City's The Village Voice or Los Angeles' LA Weekly. Major cities may also support a local business journal, trade papers relating to local industries, and papers for local ethnic and social groups. Aside from web portals and search engines, the most popular websites are Facebook, YouTube, Wikipedia, Yahoo!, eBay, Amazon, and Twitter.[559]

More than 800 publications are produced in Spanish, the second most commonly used language in the United States behind English.[560][561]

See also

- Index of United States-related articles

- Lists of U.S. state topics

- Outline of the United States

Notes

- ^ English is the official language of 32 states; English and Hawaiian are both official languages in Hawaii, and English and 20 Indigenous languages are official in Alaska. Algonquian, Cherokee, and Sioux are among many other official languages in Native-controlled lands throughout the country. French is a de facto, but unofficial, language in Maine and Louisiana, while New Mexico law grants Spanish a special status. In five territories, English as well as one or more indigenous languages are official: Spanish in Puerto Rico, Samoan in American Samoa, Chamorro in both Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands. Carolinian is also an official language in the Northern Mariana Islands.[5][6]

- ^ The historical and informal demonym Yankee has been applied to Americans, New Englanders, or northeasterners since the 18th century.

- ^ Also president of the Senate.

- ^ Hawaii

- ^ Jump up to: a b c The Encyclopædia Britannica lists China as the world's third-largest country (after Russia and Canada) with a total area of 9,572,900 km2 (3,696,100 sq mi),[15] and the United States as fourth-largest at 9,526,468 km2 (3,678,190 sq mi). This figure for the United States is less than the one cited in the CIA World Factbook because it excludes coastal and territorial waters.[16]

The CIA World Factbook lists the United States as the third-largest country (after Russia and Canada) with total area of 9,833,517 km2 (3,796,742 sq mi),[17] and China as fourth-largest at 9,596,960 km2 (3,705,410 sq mi).[18] This figure for the United States is greater than in the Encyclopædia Britannica because it includes coastal and territorial waters. - ^ Excludes Puerto Rico and the other unincorporated islands.

- ^ See Time in the United States for details about laws governing time zones in the United States.

- ^ Except the U.S. Virgin Islands.

- ^ The five major territories are American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and the United States Virgin Islands. There are eleven smaller island areas without permanent populations: Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Island, Johnston Atoll, Kingman Reef, Midway Atoll, and Palmyra Atoll. U.S. sovereignty over Bajo Nuevo Bank, Navassa Island, Serranilla Bank, and Wake Island is disputed.[14]

- ^ Spain sent several expeditions to Alaska to assert its long-held claim over the Pacific Northwest, which dated back to the 16th century. During the decade 1785–1795 British merchants, encouraged by Sir Joseph Banks and supported by their government, made a sustained attempt to develop this trade despite Spain's claims and navigation rights. The endeavors of these merchants did not last long in the face of Spain's opposition. The challenge was also opposed by a Japanese holding obdurately to national seclusion.[92]

- ^ Inupiaq, Siberian Yupik, Central Alaskan Yup'ik, Alutiiq, Unanga (Aleut), Denaʼina, Deg Xinag, Holikachuk, Koyukon, Upper Kuskokwim, Gwichʼin, Tanana, Upper Tanana, Tanacross, Hän, Ahtna, Eyak, Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian.

- ^ Source: 2015 American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau. Most respondents who speak a language other than English at home also report speaking English "well" or "very well". For the language groups listed above, the strongest English-language proficiency is among speakers of German (96% report that they speak English "well" or "very well"), followed by speakers of French (93.5%), Tagalog (92.8%), Spanish (74.1%), Korean (71.5%), Chinese (70.4%), and Vietnamese (66.9%).

- ^ People born in American Samoa are non-citizen U.S. nationals, unless one of their parents is a U.S. citizen.[358] In 2019, a court ruled that American Samoans are U.S. citizens, but the litigation is onging.[359][360]

- ^ In January 2015, U.S. federal government debt held by the public was approximately $13 trillion, or about 72% of U.S. GDP. Intra-governmental holdings stood at $5 trillion, giving a combined total debt of $18.080 trillion.[393] By 2012, total federal debt had surpassed 100% of U.S. GDP.[394] The U.S. has a credit rating of AA+ from Standard & Poor's, AAA from Fitch, and AAA from Moody's.[395]

References

- ^ 36 U.S.C. § 302

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Great Seal of the United States" (PDF). U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Public Affairs. 2003. Retrieved February 12, 2020.

- ^ Kidder & Oppenheim 2007, p. 91.

- ^ "uscode.house.gov". Public Law 105-225. uscode.house.gov. August 12, 1999. pp. 112 Stat. 1263. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

Section 304. "The composition by John Philip Sousa entitled 'The Stars and Stripes Forever' is the national march."

- ^ Cobarrubias 1983, p. 195.

- ^ García 2011, p. 167.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: United States". United States Census. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Compton's Pictured Encyclopedia and Fact-index: Ohio. 1963. p. 336.

- ^ Areas of the 50 states and the District of Columbia but not Puerto Rico nor other island territories per "State Area Measurements and Internal Point Coordinates". Census.gov. August 2010. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

reflect base feature updates made in the MAF/TIGER database through August, 2010.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2016". United States Census. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2017. The 2016 estimate is as of July 1, 2016. The 2010 census is as of April 1, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ "Income inequality". data.oecd.org. OECD. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2019" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. December 10, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ U.S. State Department, Common Core Document to U.N. Committee on Human Rights, December 30, 2011, Item 22, 27, 80. And U.S. General Accounting Office Report, U.S. Insular Areas: application of the U.S. Constitution, November 1997, pp. 1, 6, 39n. Both viewed April 6, 2016.

- ^ "China". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ "United States". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on December 19, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ "United States". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

- ^ "China". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Erlandson, Rick & Vellanoweth 2008, p. 19.

- ^ Greene, Jack P., Pole, J.R., eds. (2008). A Companion to the American Revolution. pp. 352–361.

Bender, Thomas (2006). A Nation Among Nations: America's Place in World History. New York: Hill & Wang. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-8090-7235-4.

"Overview of the Early National Period". Digital History. University of Houston. 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2015. - ^ Jump up to: a b Carlisle, Rodney P.; Golson, J. Geoffrey (2007). Manifest Destiny and the Expansion of America. Turning Points in History Series. ABC-CLIO. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-85109-833-0.

- ^ "The Civil War and emancipation 1861–1865". Africans in America. Boston: WGBH Educational Foundation. 1999. Archived from the original on October 12, 1999.

- ^ Britannica Educational Publishing (2009). Wallenfeldt, Jeffrey H. (ed.). The American Civil War and Reconstruction: People, Politics, and Power. America at War. Rosen Publishing Group. p. 264. ISBN 978-1-61530-045-7.

- ^ Judt, Tony; Lacorne, Denis (2005). With Us Or Against Us: Studies in Global Anti-Americanism. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-4039-8085-4.

Richard J. Samuels (2005). Encyclopedia of United States National Security. Sage Publications. p. 666. ISBN 978-1-4522-6535-3.

Paul R. Pillar (2001). Terrorism and U.S. Foreign Policy. Brookings Institution Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-8157-0004-3.

Gabe T. Wang (2006). China and the Taiwan Issue: Impending War at Taiwan Strait. University Press of America. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-7618-3434-2.

Understanding the "Victory Disease", From the Little Bighorn to Mogadishu and Beyond. Diane Publishing. 2004. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-4289-1052-2.

Akis Kalaitzidis; Gregory W. Streich (2011). U.S. Foreign Policy: A Documentary and Reference Guide. ABC-CLIO. p. 313. ISBN 978-0-313-38375-5. - ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2015".

- ^ "The World Factbook". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency.

- ^ "The World Factbook". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency.

- ^ "Population Clock". U.S. and World Population Clock. U.S. Department of Commerce. May 16, 2020. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

The United States population on May 23, 2020 was: 329,686,270

- ^ "Global Wealth Report". Credit Suisse. October 2018. Retrieved February 11, 2019.

- ^ "U.S. Workers World's Most Productive". CBS News. February 11, 2009. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ "Average annual wages". stats.oecd.org. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ Trends in World Military Expenditure Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

- ^ Cohen, 2004: History and the Hyperpower

BBC, April 2008: Country Profile: United States of America

"Geographical trends of research output". Research Trends. Retrieved March 16, 2014.

"The top 20 countries for scientific output". Open Access Week. Retrieved March 16, 2014.

"Granted patents". European Patent Office. Retrieved March 16, 2014. - ^ Sider 2007, p. 226.

- ^ Szalay, Jessie (September 20, 2017). "Amerigo Vespucci: Facts, Biography & Naming of America". Live Science. Retrieved June 23, 2019.

- ^ Jonathan Cohen. "The Naming of America: Fragments We've Shored Against Ourselves". Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ^ DeLear, Byron (July 4, 2013) Who coined 'United States of America'? Mystery might have intriguing answer. "Historians have long tried to pinpoint exactly when the name 'United States of America' was first used and by whom ... This latest find comes in a letter that Stephen Moylan, Esq., wrote to Col. Joseph Reed from the Continental Army Headquarters in Cambridge, Mass., during the Siege of Boston. The two men lived with Washington in Cambridge, with Reed serving as Washington's favorite military secretary and Moylan fulfilling the role during Reed's absence." Christian Science Monitor (Boston, MA).

- ^ Touba, Mariam (November 5, 2014) Who Coined the Phrase 'United States of America'? You May Never Guess "Here, on January 2, 1776, seven months before the Declaration of Independence and a week before the publication of Paine's Common Sense, Stephen Moylan, an acting secretary to General George Washington, spells it out, 'I should like vastly to go with full and ample powers from the United States of America to Spain' to seek foreign assistance for the cause." New-York Historical Society Museum & Library

- ^ Fay, John (July 15, 2016) The forgotten Irishman who named the 'United States of America' "According to the NY Historical Society, Stephen Moylan was the man responsible for the earliest documented use of the phrase 'United States of America'. But who was Stephen Moylan?" IrishCentral.com

- ^ ""To the inhabitants of Virginia", by A PLANTER. Dixon and Hunter's. April 6, 1776, Williamsburg, Virginia. Letter is also included in Peter Force's American Archives". The Virginia Gazette. 5 (1287). Archived from the original on December 19, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Safire 2003, p. 199.

- ^ Mostert 2005, p. 18.

- ^ Brokenshire 1993, p. 49.

- ^ Greg 1892, p. 276.

- ^ G. H. Emerson, The Universalist Quarterly and General Review, Vol. 28 (Jan. 1891), p. 49, quoted in Zimmer, Benjamin (November 24, 2005). "Life in These, Uh, This United States". University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- ^ Wilson, Kenneth G. (1993). The Columbia guide to standard American English. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0-231-06989-2.

- ^ Savage 2011, p. 55.

- ^ Haviland, Walrath & Prins 2013, p. 219.

- ^ Fladmark 2017, pp. 55–69.

- ^ Meltzer 2009, p. 129.

- ^ Waters & Stafford 2007, pp. 1122–1126.

- ^ Flannery 2015, pp. 173–185.

- ^ Gelo 2018, pp. 79-80.

- ^ Lockard 2010, p. 315.

- ^ Inghilleri 2016, p. 117.

- ^ Martinez, Sage & Ono 2016, p. 4.

- ^ Fagan 2016, p. 390.

- ^ Martinez & Bordeaux 2016, p. 602.

- ^ Weiss & Jacobson 2000, p. 180.

- ^ Dean R. Snow (1994). The Iroquois. Blackwell Publishers, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-55786-938-8. Retrieved July 16, 2010.

- ^ Paul Joseph (October 11, 2016). The SAGE Encyclopedia of War: Social Science Perspectives. SAGE Publications. p. 590. ISBN 978-1-4833-5988-5.

- ^ Treuer, David. "The new book 'The Other Slavery' will make you rethink American history". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- ^ Stannard, 1993 p. xii

- ^ "The Cambridge encyclopedia of human paleopathology Archived February 8, 2016, at the Wayback Machine". Arthur C. Aufderheide, Conrado Rodríguez-Martín, Odin Langsjoen (1998). Cambridge University Press. p. 205. ISBN 0-521-55203-6

- ^ Bianchine, Russo, 1992 pp. 225–232

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Perdue & Green 2005, p. 40.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Haines, Haines & Steckel 2000, p. 12.

- ^ Thornton 1998, p. 34.

- ^ Ripper, 2008 p. 6

- ^ Ripper, 2008 p. 5

- ^ Calloway, 1998, p. 55

- ^ Joseph 2016, p. 590.

- ^ "St. Augustine Florida, The Nation's Oldest City". staugustine.com.

- ^ Remini 2007, pp. 2–3

- ^ Johnson 1997, pp. 26–30

- ^ Walton, 2009, chapter 3

- ^ Lemon, 1987

- ^ Jackson, L. P. (1924). "Elizabethan Seamen and the African Slave Trade". The Journal of Negro History. 9 (1): 1–17. doi:10.2307/2713432. JSTOR 2713432.

- ^ Tadman, 2000, p. 1534

- ^ Schneider, 2007, p. 484

- ^ Lien, 1913, p. 522

- ^ Davis, 1996, p. 7

- ^ Quirk, 2011, p. 195

- ^ Bilhartz, Terry D.; Elliott, Alan C. (2007). Currents in American History: A Brief History of the United States. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1817-7.

- ^ Wood, Gordon S. (1998). The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787. UNC Press Books. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-8078-4723-7.

- ^ Walton, 2009, pp. 38–39

- ^ Foner, Eric (1998). The Story of American Freedom (1st ed.). W.W. Norton. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-393-04665-6.

story of American freedom.

- ^ Walton, 2009, p. 35

- ^ Otis, James (1763). The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved.

- ^ Pethick, Derek (1980). The Nootka Connection: Europe and the Northwest Coast 1790–1795. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-0-88894-279-1.

- ^ Pethick, Derek (1980). The Nootka Connection: Europe and the Northwest Coast 1790–1795. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-88894-279-1.

- ^ Robert J. King, "'The long wish'd for object'—Opening the trade to Japan, 1785–1795", The Northern Mariner / le marin du nord, vol. XX, no. 1, January 2010, pp. 1–35.

- ^ Collingridge, Vanessa (2003). Captain Cook: The Life, Death and Legacy of History's Greatest Explorer. Ebury Press. p. 380. ISBN 978-0-09-188898-5.

- ^ Hayes, Derek (1999). Historical Atlas of the Pacific Northwest: Maps of exploration and Discovery. Sasquatch Books. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-1-57061-215-2.

- ^ Humphrey, Carol Sue (2003). The Revolutionary Era: Primary Documents on Events from 1776 To 1800. Greenwood Publishing. pp. 8–10. ISBN 978-0-313-32083-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fabian Young, Alfred; Nash, Gary B.; Raphael, Ray (2011). Revolutionary Founders: Rebels, Radicals, and Reformers in the Making of the Nation. Random House Digital. pp. 4–7. ISBN 978-0-307-27110-5.

- ^ Greene and Pole, A Companion to the American Revolution p 357. Jonathan R. Dull, A Diplomatic History of the American Revolution (1987) p. 161. Lawrence S. Kaplan, "The Treaty of Paris, 1783: A Historiographical Challenge", International History Review, Sept 1983, Vol. 5 Issue 3, pp. 431–442

- ^ Boyer, 2007, pp. 192–193

- ^ Cogliano, Francis D. (2008). Thomas Jefferson: Reputation and Legacy. University of Virginia Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-8139-2733-6.

- ^ Walton, 2009, p. 43

- ^ Gordon, 2004, pp. 27,29

- ^ Clark, Mary Ann (May 2012). Then We'll Sing a New Song: African Influences on America's Religious Landscape. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-4422-0881-0.

- ^ Heinemann, Ronald L., et al., Old Dominion, New Commonwealth: a history of Virginia 1607–2007, 2007 ISBN 978-0-8139-2609-4, p. 197

- ^ Billington, Ray Allen; Ridge, Martin (2001). Westward Expansion: A History of the American Frontier. UNM Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8263-1981-4.

- ^ "Louisiana Purchase" (PDF). National Park Services. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ^ Wait, Eugene M. (1999). America and the War of 1812. Nova Publishers. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-56072-644-9.

- ^ Klose, Nelson; Jones, Robert F. (1994). United States History to 1877. Barron's Educational Series. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-8120-1834-9.

- ^ Winchester, pp. 198, 216, 251, 253

- ^ Morrison, Michael A. (April 28, 1997). Slavery and the American West: The Eclipse of Manifest Destiny and the Coming of the Civil War. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 13–21. ISBN 978-0-8078-4796-1.

- ^ Kemp, Roger L. (2010). Documents of American Democracy: A Collection of Essential Works. McFarland. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-7864-4210-2. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ McIlwraith, Thomas F.; Muller, Edward K. (2001). North America: The Historical Geography of a Changing Continent. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-7425-0019-8. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ Madley, Benjamin (2016). An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-23069-7.

- ^ Johansen, Bruce E.; Pritzker, Barry M. (July 23, 2007). California Indians, Genocide of. Encyclopedia of American Indian History [4 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. pp. 226–231. ISBN 9781851098187 – via Google Books.

- ^ Lindsay, Brendan C. (2012). Murder State: California's Native American Genocide, 1846–1873. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-4021-6.

- ^ Wolf, Jessica. "Revealing the history of genocide against California's Native Americans". UCLA Newsroom. Retrieved July 8, 2018.

- ^ Rawls, James J. (1999). A Golden State: Mining and Economic Development in Gold Rush California. University of California Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-520-21771-3.

- ^ Black, Jeremy (2011). Fighting for America: The Struggle for Mastery in North America, 1519–1871. Indiana University Press. p. 275. ISBN 978-0-253-35660-4.

- ^ Stuart Murray (2004). Atlas of American Military History. Infobase Publishing. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-4381-3025-5. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

Harold T. Lewis (2001). Christian Social Witness. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-56101-188-9. - ^ Jump up to: a b Patrick Karl O'Brien (2002). Atlas of World History. Oxford University Press. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-19-521921-0. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ Vinovskis, Maris (1990). Toward A Social History of the American Civil War: Exploratory Essays. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-521-39559-5.

- ^ "1860 Census" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved June 10, 2007. Page 7 lists a total slave population of 3,953,760.

- ^ De Rosa, Marshall L. (1997). The Politics of Dissolution: The Quest for a National Identity and the American Civil War. Edison, NJ: Transaction. p. 266. ISBN 1-56000-349-9.

- ^ Shearer Davis Bowman (1993). Masters and Lords: Mid-19th-Century U.S. Planters and Prussian Junkers. Oxford UP. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-19-536394-4.

- ^ Jason E. Pierce (2016). Making the White Man's West: Whiteness and the Creation of the American West. University Press of Colorado. p. 256. ISBN 978-1-60732-396-9.

- ^ Marie Price; Lisa Benton-Short (2008). Migrants to the Metropolis: The Rise of Immigrant Gateway Cities. Syracuse University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-8156-3186-6.

- ^ John Powell (2009). Encyclopedia of North American Immigration. Infobase Publishing. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-4381-1012-7. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ Winchester, pp. 351, 385

- ^ Michno, Gregory (2003). Encyclopedia of Indian Wars: Western Battles and Skirmishes, 1850-1890. Mountain Press Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87842-468-9.

- ^ "Toward a Market Economy". CliffsNotes. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ "Purchase of Alaska, 1867". Office of the Historian. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ "The Spanish–American War, 1898". Office of the Historian. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ Ryden, George Herbert. The Foreign Policy of the United States in Relation to Samoa. New York: Octagon Books, 1975.

- ^ "Virgin Islands History". Vinow.com. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ Kirkland, Edward. Industry Comes of Age: Business, Labor, and Public Policy (1961 ed.). pp. 400–405.

- ^ Zinn, 2005, pp. 321–357

- ^ Paige Meltzer, "The Pulse and Conscience of America" The General Federation and Women's Citizenship, 1945–1960," Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies (2009), Vol. 30 Issue 3, pp. 52–76.

- ^ James Timberlake, Prohibition and the Progressive Movement, 1900–1920 (Harvard UP, 1963)

- ^ George B. Tindall, "Business Progressivism: Southern Politics in the Twenties," South Atlantic Quarterly 62 (Winter 1963): 92–106.

- ^ McDuffie, Jerome; Piggrem, Gary Wayne; Woodworth, Steven E. (2005). U.S. History Super Review. Piscataway, NJ: Research & Education Association. p. 418. ISBN 0-7386-0070-9.

- ^ Voris, Jacqueline Van (1996). Carrie Chapman Catt: A Public Life. Women and Peace Series. New York City: Feminist Press at CUNY. p. vii. ISBN 978-1-55861-139-9.

Carrie Chapmann Catt led an army of voteless women in 1919 to pressure Congress to pass the constitutional amendment giving them the right to vote and convinced state legislatures to ratify it in 1920. ... Catt was one of the best-known women in the United States in the first half of the twentieth century and was on all lists of famous American women.

- ^ Winchester pp. 410–411

- ^ Axinn, June; Stern, Mark J. (2007). Social Welfare: A History of the American Response to Need (7th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. ISBN 978-0-205-52215-6.

- ^ Lemann, Nicholas (1991). The Promised Land: The Great Black Migration and How It Changed America. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-394-56004-5.

- ^ James Noble Gregory (1991). American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture in California. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507136-8. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

"Mass Exodus From the Plains". American Experience. WGBH Educational Foundation. 2013. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

Fanslow, Robin A. (April 6, 1997). "The Migrant Experience". American Folklore Center. Library of Congress. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

Walter J. Stein (1973). California and the Dust Bowl Migration. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-6267-6. Retrieved October 25, 2015. - ^ Yamasaki, Mitch. "Pearl Harbor and America's Entry into World War II: A Documentary History" (PDF). World War II Internment in Hawaii. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 13, 2014. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ Stoler, Mark A. "George C. Marshall and the "Europe-First" Strategy, 1939–1951: A Study in Diplomatic as well as Military History" (PDF). Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ^ Kelly, Brian. "The Four Policemen and. Postwar Planning, 1943–1945: The Collision of Realist and. Idealist Perspectives". Retrieved June 21, 2014.

- ^ Hoopes & Brinkley 1997, p. 100.

- ^ Gaddis 1972, p. 25.

- ^ Leland, Anne; Oboroceanu, Mari–Jana (February 26, 2010). "American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved February 18, 2011. p. 2.

- ^ Kennedy, Paul (1989). The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers. New York: Vintage. p. 358. ISBN 0-679-72019-7

- ^ "The United States and the Founding of the United Nations, August 1941 – October 1945". U.S. Dept. of State, Bureau of Public Affairs, Office of the Historian. October 2005. Retrieved June 11, 2007.

- ^ Woodward, C. Vann (1947). The Battle for Leyte Gulf. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 1-60239-194-7.

- ^ "The Largest Naval Battles in Military History: A Closer Look at the Largest and Most Influential Naval Battles in World History". Military History. Norwich University. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ "Why did Japan surrender in World War II? | The Japan Times". The Japan Times. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ Pacific War Research Society (2006). Japan's Longest Day. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 4-7700-2887-3.

- ^ Wagg, Stephen; Andrews, David (2012). East Plays West: Sport and the Cold War. Routledge. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-134-24167-5.

- ^ Blakeley, 2009, p. 92

- ^ Jump up to: a b Collins, Michael (1988). Liftoff: The Story of America's Adventure in Space. New York: Grove Press.

- ^ Winchester, pp. 305–308

- ^ Blas, Elisheva. "The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways" (PDF). societyforhistoryeducation.org. Society for History Education. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- ^ Richard Lightner (2004). Hawaiian History: An Annotated Bibliography. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-313-28233-1.

- ^ Dallek, Robert (2004). Lyndon B. Johnson: Portrait of a President. Oxford University Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-19-515920-2.

- ^ "Our Documents—Civil Rights Act (1964)". United States Department of Justice. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ "Remarks at the Signing of the Immigration Bill, Liberty Island, New York". October 3, 1965. Archived from the original on May 16, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ "Social Security". ssa.gov. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ Soss, 2010, p. 277

- ^ Fraser, 1989

- ^ Ferguson, 1986, pp. 43–53

- ^ Williams, pp. 325–331

- ^ Niskanen, William A. (1988). Reaganomics: an insider's account of the policies and the people. Oxford University Press. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-19-505394-4. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ "Women in the Labor Force: A Databook" (PDF). U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2013. p. 11. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Howell, Buddy Wayne (2006). The Rhetoric of Presidential Summit Diplomacy: Ronald Reagan and the U.S.-Soviet Summits, 1985–1988. Texas A&M University. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-549-41658-6. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ Kissinger, Henry (2011). Diplomacy. Simon & Schuster. pp. 781–784. ISBN 978-1-4391-2631-8. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

Mann, James (2009). The Rebellion of Ronald Reagan: A History of the End of the Cold War. Penguin. p. 432. ISBN 978-1-4406-8639-9.

- ^ Hayes, 2009

- ^ USHistory.org, 2013

- ^ Charles Krauthammer, "The Unipolar Moment", Foreign Affairs, 70/1, (Winter 1990/1), 23–33.

- ^ "Persian Gulf War". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Winchester, pp. 420–423

- ^ Dale, Reginald (February 18, 2000). "Did Clinton Do It, or Was He Lucky?". The New York Times. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

Mankiw, N. Gregory (2008). Macroeconomics. Cengage Learning. p. 559. ISBN 978-0-324-58999-3. Retrieved October 25, 2015. - ^ "North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) | United States Trade Representative". www.ustr.gov. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

Thakur; Manab Thakur Gene E Burton B N Srivastava (1997). International Management: Concepts and Cases. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. pp. 334–335. ISBN 978-0-07-463395-3. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

Akis Kalaitzidis; Gregory W. Streich (2011). U.S. Foreign Policy: A Documentary and Reference Guide. ABC-CLIO. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-313-38376-2. - ^ Flashback 9/11: As It Happened. Fox News. September 9, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

"America remembers Sept. 11 attacks 11 years later". CBS News. Associated Press. September 11, 2012. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

"Day of Terror Video Archive". CNN. 2005. Retrieved March 6, 2013. - ^ Walsh, Kenneth T. (December 9, 2008). "The 'War on Terror' Is Critical to President George W. Bush's Legacy". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

Atkins, Stephen E. (2011). The 9/11 Encyclopedia: Second Edition. ABC-CLIO. p. 872. ISBN 978-1-59884-921-9. Retrieved October 25, 2015. - ^ Wong, Edward (February 15, 2008). "Overview: The Iraq War". The New York Times. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

Johnson, James Turner (2005). The War to Oust Saddam Hussein: Just War and the New Face of Conflict. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-7425-4956-2. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

Durando, Jessica; Green, Shannon Rae (December 21, 2011). "Timeline: Key moments in the Iraq War". USA Today. Associated Press. Retrieved March 7, 2013. - ^ Wallison, Peter (2015). Hidden in Plain Sight: What Really Caused the World's Worst Financial Crisis and Why It Could Happen Again. Encounter Books. ISBN 978-978-59407-7-0.

- ^ Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (2011). Financial Crisis Inquiry Report (PDF). ISBN 978-1-60796-348-6.

- ^ Taylor, John B. (January 2009). "The Financial Crisis and the Policy Responses: An Empirical Analysis of What Went Wrong" (PDF). Hoover Institution Economics Paper Series. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ^ Hilsenrath, Jon; Ng, Serena; Paletta, Damian (September 18, 2008). "Worst Crisis Since '30s, With No End Yet in Sight". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ^ "Barack Obama elected as America's first black president". History.com. A&E Television Networks, LLC. October 31, 2019. Retrieved November 11, 2019.

- ^ "Barack Obama: Face Of New Multiracial Movement?". NPR. November 12, 2008. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ^ Washington, Jesse; Rugaber, Chris (September 9, 2011). "African-American Economic Gains Reversed By Great Recession". Huffington Post. Associated Press. Archived from the original on June 16, 2013. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ^ Shanker, Thom; Schmidt, Michael S.; Worth, Robert F. (December 15, 2011). "In Baghdad, Panetta Leads Uneasy Closure to Conflict". The New York Times.

- ^ Cooper, Helene (May 1, 2011). "Obama Announces Killing of Osama bin Laden". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 2, 2011. Retrieved May 1, 2011.

- ^ Martin, Emmie (January 23, 2017). "Donald Trump is officially the richest US president in history". Business Insider. Retrieved November 12, 2019.

- ^ Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, Lofy KH, et al. (March 2020). "First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States". N. Engl. J. Med. 382 (10): 929–936. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. PMC 7092802. PMID 32004427.

- ^ https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/us/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ "Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report – 89" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 18, 2020. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- ^ "Field Listing: Area". The World Factbook. cia.gov.

- ^ "State Area Measurements and Internal Point Coordinates—Geography—U.S. Census Bureau". State Area Measurements and Internal Point Coordinates. U.S. Department of Commerce. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ "2010 Census Area" (PDF). census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. p. 41. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- ^ "Area". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ^ "United States". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 8, 2018. (given in square miles, excluding)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "United States". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. January 3, 2018. Retrieved January 8, 2018.